On World Press Freedom Day's eve in Brisbane, the Australian journalists union - Media, Arts and Entertainment Alliance (MEAA) - threw a party for media and UNESCO delegates attending the two-day conference at the University of Queensland. A "South Pacific soirée". The latest "press freedom" edition (May/June) of the Walkley Magazine was launched there. Along with a 13-page report card on the state of media freedom in Australia, the following article on Fiji was published:

No colonel of truth in Fiji

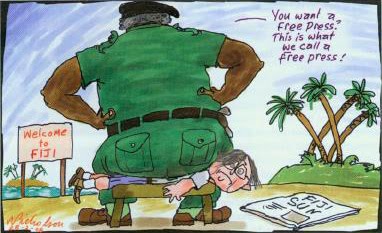

For a year, journalists in Fiji have had to live with censors posted in the newsroom. Now a new media decree threatens huge fines and and five years in prison for reports against the national interest. It's a dangerous precedent for the entire Pacific region, says David Robie. Cartoon by Peter Nicholson.

When an Indo-Fijian academic and former trade unionist turned up on Fiji’s shores from Hawaii by invitation to conduct a media industry “review” in June 2007, few took him seriously. Whatever Dr James Anthony’s expertise in other fields, news media was certainly not one of his strengths. Also, it had been decades since he had lived in Fiji and he seemed out of touch.

And then there was a niggling question about the legitimacy of his mission. He had been commissioned by then Fiji Human Rights Commission director Dr Shaista Shameem – no friend of Fiji news organisations – to study media freedom and the future of the industry in the Pacific country.

“Negative reactions of the media industry to human rights scrutiny in the public interest are not unique to Fiji,” Shameem said. “Other human rights commissions have faced similar obstacles – such as the South African Human Rights Commission.”

Anthony immediately clashed with local news media companies and the self-regulatory Fiji Media Council and they refused to cooperate with him. He persevered in an atmosphere of hostility and produced a 161-page report branded by his opponents as “racist” – for a sweeping claim that the industry was dominated by eight white expatriates – and “riddled with inaccuracy”.

Ironically titled “Freedom and independence of the media in Fiji”, the report was discredited and appeared to have sunk into oblivion. Yet now Anthony has come back into focus. His recommendations were adopted as the basis of a draconian draft decree widely regarded as a sinister threat to the future of a free press in Fiji and across the South Pacific.

Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum claimed the Media Industry Development Decree 2010 “takes the already established rules of professionalism, of media behaviour – or how they should behave – and gives it teeth”.

Decree 'teeth'

The “teeth” includes rolling Anthony’s primary proposals for a Singapore-inspired Media Development Authority and an “independent” Media Tribunal into this proposed law along with a radical curb on foreign ownership, wide powers of search and seizure and harsh penalties for media groups and journalists breaching the decree.

The authority and tribunal would be empowered to fine news organisations up to F$500,000 and to fine individual journalists and editors up to F$100,000 – or imprison them for up to five years – for violations of vaguely defined codes such as publishing or broadcasting content that is “against public order”, “against national interest” or “creates communal discord”.

Foreign ownership is retrospectively restricted to a 10 percent stake in any media organisation and directorships must only go to Fiji citizens who have been residing in the country for five of the past seven years, and nine of the past 12 months.

Many critics see this as a vindictive section aimed at crippling the Fiji Times, the country’s largest and most influential newspaper and owned by a Murdoch subsidiary, News Limited.

The regime wants to put the newspaper, founded at Levuka in 1869, out of business, or at least effectively seize control and muzzle its independent stance – seen by the military-backed government as “anti-Fiji”.

Two Australian publishers of the Fiji Times have been deported on trumped up grounds since military commander Voreqe Bainimarama staged the country’s fourth coup in December 2006. The High Court also imposed a hefty F$100,000 fine against the Fiji Times in early 2009 for publishing an online letter criticising the court for upholding the legality of the 2006 coup.

While international responses have focused on the serious impact for the Fiji Times group, the terms of the decree will also hit the country’s two other dailies – the struggling Fiji Daily Post (it hasn't been publishing lately), which has 51 percent Australian ownership, and the Fiji Sun, which has taken a distinctly “pro-Fiji” (that is, pro-regime) stance but also has some expatriate directors.

John Hartigan, chief executive of the Fiji Times' parent company News Limited, warned the decree raised “important commercial issues” for the newspaper. “We have made representations to the Fiji authority to find a way to resolve these issues and are awaiting the outcome,” he said.

Mixed responses

The draft decree follows 12 months of “sulu censors” - so-called because of the traditional Fijian kilt-like garment some officials wear - keeping tabs on newsrooms after the 1997 constitution was abrogated by the regime in April last year and martial law declared.

Responses to the proposed law have been mixed within Fiji, but other media groups have strongly condemned it. Paris-based Reporters Without Borders criticised the regime for tightening its grip on media, noting that Fiji had fallen 73 places in its annual freedom rankings. Fiji is now placed 152nd out of 175 countries.

The Pacific Media Centre branded the draft decree as “draconian and punitive” and the Pacific Freedom Forum said it would “deal a death-blow to freedoms of speech”. The International Federation of Journalists criticised the regime for investing authorities with the power to define the meaning of “fair, balanced and quality” journalism.

Most Fiji journalists were reluctant to speak out publicly with their jobs potentially on the line. But many contributed postings to some of the 72 post-coup blogs about Fiji or shared insights with their Pacific colleagues on cyberspace networks.

Dangerous precedent

Other Pacific journalists see the draft law as a dangerous precedent for the region, one that could be emulated by unscrupulous politicians in other countries as a strategy to control the media.

Already the Suva-based Pacific Islands News Association (PINA) and its regional news cooperative Pacnews are facing a dilemma – to stay and risk being compromised, or to leave but have less lobbying influence on the regime. Vice-president John Woods, editor of the Cook Islands News, has called on the organisation to relocate out of Fiji, describing PINA as “dysfunctional” and “kowtowing” to the regime.

One Suva old hand who had been a star reporter at the time of the first two coups in 1987 admitted there were some good aspects to the decree, such as encouraging training and enforcing the codes of ethics: “But it simply continues the censorship – although now in a camouflaged form.”

Walkley Foundation