Pacific Journalism Review is a very successful journal which continues to play a vital role publishing papers from and about this part of the world, writes Australian Journalism Review editor Professor Ian Richards.

I am delighted to be able to join you to celebrate this major milestone in the development of Pacific Journalism Review.

But before I say more about that, I would like to extend my congratulations to Auckland University of Technology for winning the bid to host the 2016 World Journalism Education Congress. As an executive member of the WJEC, I can say unequivocally that this a great achievement for AUT and for Associate Professor Verica Rupar, who led the AUT bid.

Today, however, we are here to honour a very successful academic journal. In doing so, a logical starting point might be to ask: what is an academic journal?

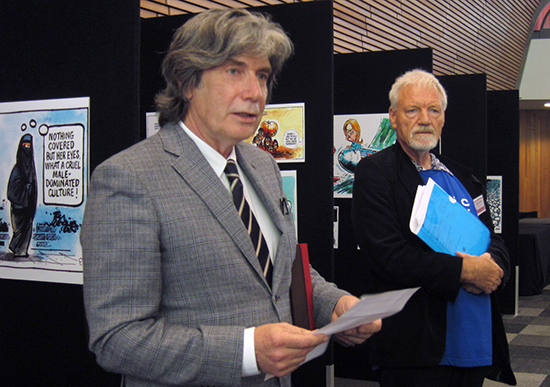

One good definition is that a journal is ‘a vehicle of scholarly communication where the latest thinking and research can be disseminated, discussed and reviewed, to and by others in the same field’. I’m pleased to say that PJR fits this description very well, and has done so for two decades. The next question we might ask is: what is an editor? I believe it was T. S. Eliot who once remarked that "all editors are failed writers”, before adding – "but then, so are most writers". I’ll leave it to you to decide for yourselves whether David Robie and I fit this description.

The next question we might ask is: what is an editor? I believe it was T. S. Eliot who once remarked that "all editors are failed writers”, before adding – "but then, so are most writers". I’ll leave it to you to decide for yourselves whether David Robie and I fit this description.

Journal editors are often described as gatekeepers, but I prefer "enablers" because we enable academics and researchers to have their work published. We provide a platform for sharing the fruits of their research, and, indeed, we also provide a specialised audience for this research.

Common issues

In general, as journal editors, we have many common issues to contend with. These include:

• Limited time and resources – good editing requires both, but both are not always available.

• A rapidly increasing number of submissions – apart from an associated increase in workload, this also raises issues of quality because, unfortunately, more papers does not necessarily mean more quality.

• Increased pressure from authors for quick responses. Greater pressure on academics to publish means greater pressure on editors from authors who want to know if their work will see the light of day – or, alternatively, if it needs to be submitted elsewhere in order to do so.

• Reviewer issues. Quality and consistency are ongoing concerns. Good reviewers not only need to know their field, but they also need to be reliable, capable, able to meet deadlines, and – when necessary – able to reject papers in terms which are balanced rather than brutal. Reviewers, too, have heavy workloads, so it is also important not to overload particular reviewers because they might be particularly good at it.

• Transparency. Plagiarism and copyright infringement are only two of the dangers lurking in the world of the academic paper.

• Publication and circulation. Editors have to deal with matters of funding, as well as editorial boards, lawyers (on occasion), and issues involving database access and commercial publishers.

• Institutional constraints. Most editors are employed by universities, and thus have to meet institutional requirements and demands. These are not always conducive to editing an academic journal.

A few pressures

These matters affect most, if not all, journal editors. But in addition, there are a few pressures which are faced by just a few of us, including David and myself, and we have to respond to them as best we can.

When I say "we", I am reminded of Mark Twain’s observation that "Only kings, presidents, and people with tapeworms have the right to use 'we'"- but I think it’s okay here.

Many of these extra pressures are a product of our geography and history. Australia and New Zealand are economically and politically part of the Global North, but we are so far from the US and Europe that many of us feel we are living on the periphery.

This feeling is exacerbated by a lingering inheritance from colonial days of what in Australia we call the "cultural cringe", meaning that things produced in the northern hemisphere are somehow automatically considered to be better than things produced in the southern hemisphere.

This unjustified feeling of inferiority is behind many of the debates about whether our local journals are as good as ‘international’ journals. And in most cases, the latter are really only the northern hemisphere’s version of ‘local’ journals anyway.

Also related to the realities of geography is the fact that – for obvious reasons - most academics ground their research in situations with which they are most familiar. This often means they produce articles which are extremely local.

But if "local" means London or Paris or New York, then it’s much easier to present your work as "international" than if you live in Port Villa or Pago Pago, or, for that matter, Auckland or Adelaide.

Other obstacles

At the same time, many authors based in the Global South have to contend with obstacles which are unknown in the Global North, meaning everything from limited access to computers and inadequate infrastructure to frequent power blackouts, physical danger and political instability.

Finally, there is what I would describe as plain old-fashioned ignorance on the part of many of our colleagues in the Global North. As a demonstration of this, earlier this year I was discussing possible venues for the 2016 WJEC with northern hemisphere colleagues. When I mentioned that New Zealand was a contender for the event, which is only held every three years, one of them said something to the effect that – "Well, WJEC was in Singapore in 2007, so that part of the world has had its turn".

These colleagues were shocked when I pointed out that the distance from Auckland to Singapore is about 8500 kilometres. By comparison:

• London to Moscow is 2500 kilometres.

• London to New York 5500 kilometres.

• London to New Delhi 6700 kilometres.

• London to San Francisco 8600 kilometres – only 100 kilometres further than Auckland to Singapore.

Matured immensely

PJR has successfully negotiated a way through all of these pressures and problems. It has matured immensely as it has moved from the University of Papua New Guinea in Port Moresby to the University of the South Pacific in Suva, Fiji, and eventually to New Zealand and the Pacific Media Centre here at AUT.

It has consistently published papers relating not only to New Zealand, but also to Australia as well as the huge area of the globe known as Oceania. In doing so, it has helped address the gross imbalance in academic publishing between the Global North and the Global South and – along the way – also demonstrated the validity of journalism practice as a research methodology.

In short, PJR is a very successful journal which continues to play a vital role publishing papers from and about this part of the world.

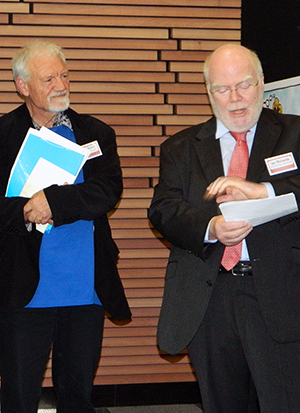

Throughout its two decades of existence, the journal has been edited by the indefatigable David Robie, who recently – and deservedly – was appointed New Zealand’s first professor of journalism. The success of PJR is a tribute to David’s commitment, talent and dogged perseverance.

Congratulations, David, and congratulations to all of your colleagues who have helped bring about this success.

Best of luck for the next 20 years!

Professor Ian Richards is editor of the Australian Journalism Review and professor of journalism at the University of South Australia, Adelaide. This was address was presented at the Pacific Journalism Review 20th Anniversary conference at AUT University.

PJR2014

Media freedoms, human rights and doco feature in PJR conference

Grim reminders of price paid by journalists in Asia-Pacific

PMC, RSJ call for action on Ampatuan massacre trial

Fiji media still face 'noose around neck' challenges

Max Stahl's livestreaming

Walter Fraser's opening speech

Max Stahl tells of Santa Cruz massacre on Radio NZ's Sunday

Green MP calls for 'rigorous documentation' Pacific sequel to Hot Air film

PJR2014 on Storify

PJR website