David Ingram profiles the life and times of cartoonist Bob Browne, the "social conscience" of Papua New Guinea.

An era of sorts came to an end this week with the death of cartoonist Bob Browne in Port Moresby General Hospital. He was the creator of Mista Grasruts (Grass Roots), perhaps Papua New Guinea’s most loved comic character, which the magazine Islands Business once called “the social conscience of PNG”.

He was the creator of Mista Grasruts (Grass Roots), perhaps Papua New Guinea’s most loved comic character, which the magazine Islands Business once called “the social conscience of PNG”.

Browne’s life and work could almost be read as an allegory of change in the Pacific Islands’ largest nation. Browne arrived in PNG as a British volunteer in 1971 when the country was preparing excitedly for independence and he stayed with his adopted homeland through thick and thin until his death.

It is tempting to write that he saw the country change beyond recognition in the intervening 40 years but he also witnessed its failure to advance in some important ways, especially in areas of social justice and the fight against corruption, both issues which he and his sidekick Grass Roots cared deeply about in their own ways.

Roots became the Papua New Guinean Everyman, the knock-about character with a heart of gold, a belly full of beer and a thick skull where his long-suffering wife, Agnes, berated his foolishness with her famous “sospen”.

Through Roots – who started as a character called Lu promoting Isuzu trucks – Browne was able to reflect on PNG life through an eerily indigenous perspective and criticise its shortcomings in a gentle but incisive way.

Pot-shots at the gross

The great strength of cartooning is the ability to take pot-shots at the gross, the venal, the dishonest, the lazy or the plain foolish from behind the protective ramparts of humour. Browne seldom let this advantage descend into bitterness or cruelty, thanks mainly to Grass Roots himself, a man both naive and aware, a hale and hearty innocent wandering through a confused and confusing world.

In Australia, Roots would be called “a good bloke”, in the US “a good ol’ boy”, someone you felt drawn to protect even though you’d also harbour the suspicion he was in some mysterious way already ahead of you.

In Australia, Roots would be called “a good bloke”, in the US “a good ol’ boy”, someone you felt drawn to protect even though you’d also harbour the suspicion he was in some mysterious way already ahead of you.

Browne achieved this partly through a unique, instantly-recognisable drawing style – like all great cartoonists you only had to see one frame to know immediately who the artist was – and partly because, from the first Isuzu Lu cartoon in 1980, his characters spoke with an uncannily accurate urban Papua New Guinean patois, a kind of pidgin Pidgin, accessible to almost anyone in the country, high or low, who could read.

That all this could be achieved by a white man born in London was an added facet of Browne’s character, not because he was especially enigmatic or complex – friends denied Browne was an especially complicated man, just a busy one – but because he really was an example of what-you-see-is-what-you-get.

If he wore his heart on his sleeve as a cartoonist, that was because it was just too big for his spare frame. A youthful trip through Morocco in 1970, where he was deeply shaken by the poverty he witnessed, led him to volunteer his skills as a graphic designer to the British agency Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO), which sent him to PNG to work for the Catholic Mission’s Wirui Press.

He began drawing cartoons for Wantok newspaper, which was published in Tok Pisin, what was to become one of the new nation’s three national languages along with English and Motu. After two years he moved to the capital Port Moresby where he helped to establish a new Centre for Creative Arts.

It was an exciting, optimistic period in PNG, with the peaceful transition to independence from Australia and the handover of the nation to mainly young indigenous men and women. What they lacked in skills and experience, they made up for in energy and youthful idealism. Even their first Prime Minister, Michael Somare, was only 39 at Independence.

Many volunteers

The national watch cry was “Go ahead strong!” and as the expatriates withdrew south of the Torres Straits, many were replaced by volunteers from around the world, mainly from Australia, Britain, Canada, the US and – through various religious or political organisations – Western Europe.

We all knew our jobs were only meant to be temporary and most of us left when our time finished, but others, such as Browne, were seduced by the country, its climate, its natural beauty, exotic cultures and, most of all, by its friendly and welcoming people. Browne would eventually take PNG citizenship and marry into a local family. When the Centre for Creative Arts became the National Arts School, Browne became Head of the Graphics Department. In 1980 he started drawing daily Grass Roots cartoons for the Post-Courier newspaper, and a year later started his own Grass Roots Comic Company. As well as his media cartoons, he produced spin-off works such as anthologies of his work, illustrations for numerous books and booklets and, most famously, The Grass Roots Guide to Papua New Guinea Pidgin, a grand title to a slim booklet in which Roots explained in his own, inimitable way the meaning of terms such as “Mauswara – Like smok out the eksost pipe of a PMV it’s coming out the mouth of most polly boys when somebody turn on their hignition.” The entry was accompanied by a cartoon of a bloated, suited politician floating like a balloon above a small boy with a bow and arrow.

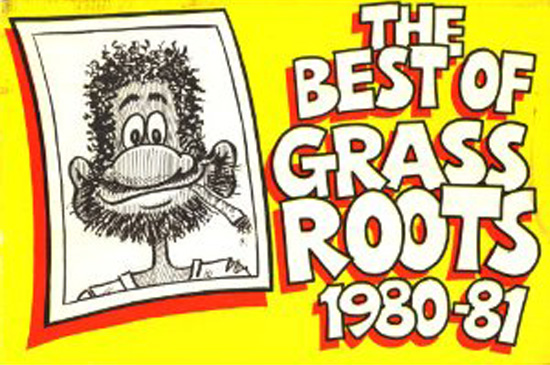

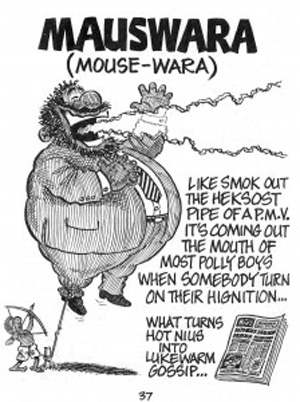

When the Centre for Creative Arts became the National Arts School, Browne became Head of the Graphics Department. In 1980 he started drawing daily Grass Roots cartoons for the Post-Courier newspaper, and a year later started his own Grass Roots Comic Company. As well as his media cartoons, he produced spin-off works such as anthologies of his work, illustrations for numerous books and booklets and, most famously, The Grass Roots Guide to Papua New Guinea Pidgin, a grand title to a slim booklet in which Roots explained in his own, inimitable way the meaning of terms such as “Mauswara – Like smok out the eksost pipe of a PMV it’s coming out the mouth of most polly boys when somebody turn on their hignition.” The entry was accompanied by a cartoon of a bloated, suited politician floating like a balloon above a small boy with a bow and arrow.

He also defined Mauswara (derived from the English “mouth water”) as “What turns hot nius into lukewarm gossip”, demonstrating an understanding of the media which endeared him to a generation of young Papua New Guinean journalists and which made him our only choice as illustrator when the late Peter Henshall and I published the journalism textbook The News Manual through the University of PNG. The three-volume handbook went into every newsroom and journalism training programme in the Pacific Islands region and while it contained hundreds of pages of excellent advice, most readers still mainly remember it for Bob Browne’s brilliant cartoons.

When asking Browne to produce 21 cartoons for the book, we fretted about the wisdom of two white men asking a third white man – albeit by that time a naturalised Papua New Guinean – to draw humorous cartoons of obviously dark-skinned people to illustrate key issues in journalism. To this day we seem to have been the only people who’ve ever been worried by it; Browne’s drawings were so clever, his characters so convincing and the message so transparently well-meant that it was never an issue.

Tilting at windmills

Browne could easily have been a success in the much larger media ponds of Britain or Australia, but instead in 1990 he chose to become a PNG citizen and re-joined the National Arts School as Head of Visual Arts as it was being integrated into the University of PNG.

He and Grass Roots continued to tilt at the windmills of a declining public service, the waste of abundant national resources and escalating lawlessness which he felt were largely fed by corruption and greed amongst leaders and others in authority who should have been setting a better example. While many expatriates “went finish” disillusioned, Browne threw himself into even more practical works in an attempt to stem the tide. He worked as a church pastor, teacher, counsellor, overseas missionary and manager of Port Moresby City Mission, all the while keeping up his love of cartoons.

He was a keen player, coach and supporter of basketball and soccer, which he saw as great ways to engage with the young and the disenfranchised. He served on government advisory bodies and received PNG’s 10th Anniversary of Independence Medal for Services to the Community, a small official recognition for the years of service and entertainment he had provided the nation.

In 2006, he developed a tumour on his neck which proved to be cancerous and although he underwent a number of operations and drew on the prayers and support of an international network of friends and admirers, it finally overwhelmed him and he died in Port Moresby General Hospital in the early hours of 2 March 2011.

Bob Browne leaves his wife, Segana, their 15-year-old son, David, and a multitude of friends and fans in Papua New Guinea and around the globe.

The world is a poorer, less interesting place without him and one can only wonder what Grass Roots might have said about it all.

David Ingram is an independent journalist, co-author of The News Manual, and a former lecturer in journalism at the University of Papua New Guinea. This tribute is republished with permission from his blog DogBitesMan.