La Troisième Équipe—Souvenirs de l’Affaire Greenpeace, by Edwy Plenel. Paris : France. Editions Don Quichotte, 2015, 140 pp. ISBN 978-235-949-462-4

Reviewed by RÉMI PARMENTIER

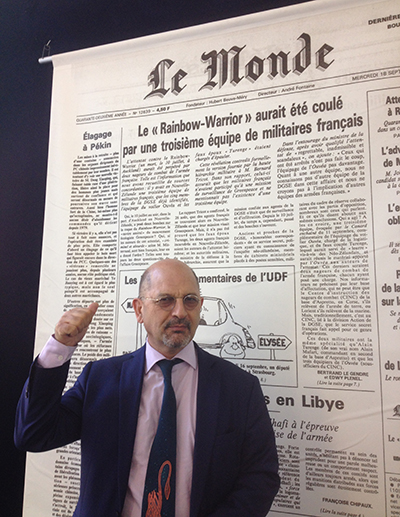

BOOK REVIEW: IF YOU visit the headquarters of the newspaper Le Monde in Paris, on the wall facing you in the main hall after you’ve passed security you’ll find, side-by-side, the large reproductions of two covers of the daily newspaper which has been for decades the hallmark of the French intelligentsia. Testimonies of passed times, nearly three decades separate the one on the right side of the wall, ‘Marshal Stalin has died’ (March, 1953) from the one on the left, ‘The Rainbow Warrior would have been sunk by a third team of French military’ (September, 1985).

Why did someone choose to juxtapose two stories that bear no relation? Maybe it is because both events marked a new point of departure in the psyche of the Parisian left: Stalin’s death opened the key to the Soviet Pandora's box, and the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior 30 years ago by a French secret service squad in Auckland harbour to prevent Greenpeace from protesting against nuclear weapons testing in French Polynesia is now seen as the most grotesque illustration of François Mitterrand’s presidency (1982-1995) renunciation of his Socialist Party’s stated values.

Why did someone choose to juxtapose two stories that bear no relation? Maybe it is because both events marked a new point of departure in the psyche of the Parisian left: Stalin’s death opened the key to the Soviet Pandora's box, and the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior 30 years ago by a French secret service squad in Auckland harbour to prevent Greenpeace from protesting against nuclear weapons testing in French Polynesia is now seen as the most grotesque illustration of François Mitterrand’s presidency (1982-1995) renunciation of his Socialist Party’s stated values.

The Rainbow Warrior front page story was the outcome of weeks of investigation by Edwy Plenel, then a young reporter in his early thirties and now 30 years later, the founding director of Mediapart, the leading French investigative news online publication.

World reflections

On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the Rainbow Warrior bombing, in La Troisième Équipe- Souvenirs de l’Affaire Greenpeace Plenel shares anecdotes and reflects on the ways the world has changed since that time, for better or

worse—mostly worse.

Plenel’s book should be on a list of recommended reading for all young journalists, political scientists and politicians who have reached adulthood only after the internet and the end of the Cold War changed the way global political action and communication takes place.

‘The landscape of the Greenpeace affair is a world that is reaching its end and does not know it,’ writes Plenel three decades later. ‘The tension around nuclear weapons and the disregard for environmental challenges, the political resort of state terrorism by the French state in New Zealand was anchored in this old world.’ (p. 23).

In ‘A Story from Before’, the first of four chapters, Plenel reminds us that it took four weeks for Le Monde to figure out that what had happened in Auckland, in the antipodes had a French political dimension; four weeks during which the newspaper had only published a handful of brief agency dispatches, with the exception of a larger piece from Le Monde’s environment correspondent. The sinking of the Rainbow Warrior took place on 10 July 1985; Plenel explains in the book that it was almost by accident this story fell on his desk, at a time when the newspaper’s offices had been largely deserted in August for the summer holiday.

Jigsaw puzzle

Chapters 2 to 4 contain Plenel’s first-hand account on how he collected one by one what he describes as the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. He was supported and worked in synergy with a few journalist colleagues from within and outside his own newspaper, but he also describes how his work was undermined and sabotage was attempted by many other French journalist colleagues whose goal was obviously to deliberately conceal the truth in order to protect the military.

Indeed the strong ties, at least at the time, between French media and the country’s secret services was, during the summer of 1985 one of the most destabilising factors for everyone involved closely or remotely in trying to uncover the truth—the author of this book review included.

Plenel also refreshes our memories with his description of the infamous Tricot report, named after Bernard Tricot, a former close collaborator and political appointee of General de Gaulle in the sixties and a member of the Council of State (the French equivalent of the Supreme Court for administrative justice) at the time of the Rainbow Warrior affair. In a desperate attempt to cover up, President Mitterrand commissioned Tricot to undertake an ‘investigation’.

Plenel also refreshes our memories with his description of the infamous Tricot report, named after Bernard Tricot, a former close collaborator and political appointee of General de Gaulle in the sixties and a member of the Council of State (the French equivalent of the Supreme Court for administrative justice) at the time of the Rainbow Warrior affair. In a desperate attempt to cover up, President Mitterrand commissioned Tricot to undertake an ‘investigation’.

Released on August 25, little more than 6 weeks after the explosion of the Rainbow Warrior in Auckland, the Tricot report concluded that, if French agents were present in Auckland at the time of the Rainbow Warrior bombing, it was only to watch (spy on) the Greenpeace vessel, not to attack it.

Only those who wanted (or were told) to believe Tricot did, but the vast majority took his report for what it was: a gross, utterly predictable whitewash.

Nothing conclusive

In the three weeks and a half that followed after Tricot, there was a race among a handful of French journalists to get to the bottom of the truth. Bits and pieces were released here and there. But nothing conclusive until Edwy Plenel signed (under the supervision of his boss, the head of the newspaper’s Justice Section Bertrand Le Gendre who was co-signatory) the outcome of his investigation which was published on September 17: ‘The Rainbow Warrior would have been sunk by a third team of French military.’

Until then, everyone had paid attention on two different teams of French agents in Auckland: the false ‘Turenge’ couple that was arrested in Auckland almost immediately after the bombing, and another group that had come from New Caledonia on a yacht, the Ouvéa, and which had escaped from New Zealand, and later Norfolk Island, in time to be rescued by a French nuclear submarine in the high seas.

Both groups had played a role, but they both had covers to suggest that they could not have possibly dived under the hull of the Rainbow Warrior to fix the two limpet mines with which she was sunk.

Figured it out

By uncovering a third team, Plenel caused the collapse of the fragile house of cards assembled by French authorities to cover their backs. The Ouvéa team’s mission was ‘only’ to sail into New Zealand with the two bombs on board; the ‘Turenges’ role was ‘only’ to catch up with the Ouvéa outside Auckland and to deliver the bombs to the third team that had gone unnoticed until Plenel figured it out.

In his book, La Troisième Équipe (The Third Team), Plenel explains that in the first draft of his story he was not using the conditional tense ‘…would have been sunk by a third team…’ that was imposed by the newspaper’s executives. However that was enough to unmask the truth. It took 48 hours after the release of Plenel’s story for Prime Minister Fabius to sack Charles Hernu, the Defence Minister, and Admiral Pierre Lacoste, the head of the secret services.

Many of the protagonists of the Rainbow Warrior affair are now dead. The former Defence Minister, Charles Hernu was the first one to go, in 1990. François Mitterrand also died in 1996, of course, but remained President of the Republic until 1995.

In 2005, nine years after Mitterrand’s death and 20 years after the Rainbow Warrior bombing, Le Monde published a leaked document that proved that in 1986 the head of the secret services Pierre Lacoste had testified in a classified document commissioned by a new Defence Minister, that President Mitterrand had been aware of early on and had approved the plan to sink the Rainbow Warrior. ‘I would not have undertaken such an operation without the personal authorisation of the President of the Republic,’ Lacoste was reported as saying.

Poisonous affair

One character who is still alive and well is Laurent Fabius, then the youngest ever French Prime Minister who was in his late thirties in 1985. It is generally thought, unless proven wrong, that Fabius inherited this poisonous affair and had been kept in the dark by President Mitterrand until it took place, some say even until Plenel’s story came out.

Thirty years later, Fabius is currently President François Hollande’s Foreign Affairs Minister, and as such he will be chairing the critical Paris Climate Summit in December this year. Fabius is deploying great efforts to make the so-called COP 21 Climate Summit a resounding success. It is too early to know whether he will succeed, but his eagerness to be seen as a green leader on the world stage is a good illustration of the way the political environment is changing—in this case for the best, we hope.

There is one other character who is still alive, according to Plenel. Throughout the book, Plenel calls him le Consul, the Consul. That was Plenel’s informer from within the French administration, throughout in that summer of 1985. Rather than a straight informer, Plenel describes him more like a guide or a coach who puts him on the right tracks, and warns him when he’s making a wrong turn. Very much like the ‘deep throat’ of Bob Woodward and Carl Berstein of The Washington Post during Watergate. But with a notable and very French difference: Plenel was meeting his deep throat in exquisite Parisian restaurants apparently, not in a parking lot like Woodward and Bernstein. Ah … Paris sera toujours Paris!

RÉMI PARMENTIER is director of the Varda Group, an international strategic consultancy specialising in environmental advocacy and project development www.vardagroup.org. He was a veteran of early Greenpeace campaigns on board the original Rainbow Warrior in the 1970s and early 1980s, and later Greenpeace International’s political director. This review was commissioned by Pacific Journalism Review and will appear in the next edition.

Twitter: @RemiParmentier

30 years on, French bomber apologises for sinking the Rainbow Warrior