SPECIAL REPORT: By David Robie, who sailed on the original Rainbow Warrior to Rongelap atoll and is author of the book Eyes of Fire.

Thirty five years ago today the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior was bombed in Auckland’s Waitematā Harbour by French secret agents in a blatant act of state terrorism, killing a photojournalist.

People’s campaigns have moved on since then from nuclear tests and refugees to climate justice – and future Pacific refugees.

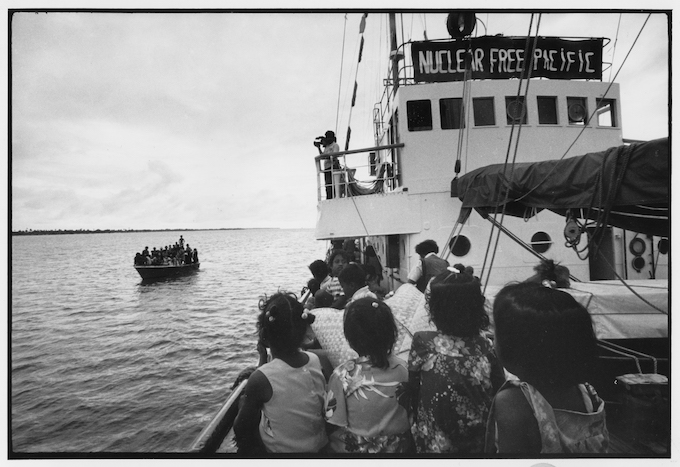

The environmental campaign flagship was bombed on 10 July 1985 just weeks after it had been in the Marshall Islands carrying out four humanitarian voyages to rescue more than 320 Rongelap atoll villagers from the ravages of US nuclear tests and take them to a new home, Mejato island on Kwajalein atoll.

READ MORE: Eyes of Fire – Thirty Years On

LISTEN: David Robie reflects on the Rainbow Warrior on RNZ’s Crimes NZ programme

They were nuclear refugees seeking justice, relief and a healthy life far from the dangerous legacy left from 105 tests on Bikini and nearby atolls.

Ironically, the bombing in Auckland and mounting Pacific opposition led to a massive wave of New Zealand and Pacific anti-nuclear solidarity and ultimately to the halt of French nuclear testing at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls in 1996 after 193 blasts.

The bombed ship’s pioneering environmental work has since been carried on by Rainbow Warrior II and the state-of-the-art eco campaign ship Rainbow Warrior III.

Today the focus is on climate refugees, the lack of adequate health compensation for the Polynesians who suffered radiation and failure to provide proper clean-up of the French nuclear testing zones that are still off-limits after almost a quarter century. Tests were carried out by balloon, derrick, in the lagoon and in a series of underground shafts which have threatened the stability of the 60 km long atoll, leaving it fractured “like Swiss cheese”.

Landmark ruling

In January this year, in a landmark United Nations ruling, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, governments have been told not to return people to countries where their lives might be threatened by climate change.

Climate action activists have greeted this ruling as a potential game changer for both climate refugees, or migrants, and for advocates for global climate action.

The UN Human Rights Committee ruled in the covenant that “without robust national and international efforts, the effects of climate change in receiving states may expose individuals to violations of their rights”.

The ruling applied to a humble New Zealand vegetable farm foreman, Ioane Teitiota, from the island nation of Kiribati, who had become a poster boy for climate refugee legal advocates even though he had little understanding of this concept.

Five years earlier, his lawyers had applied for protection for him in New Zealand after presenting a legal argument that he and his family’s lives were at risk from the impact of climate change and rising Pacific Ocean level in Kiribati as one of the “frontline states” facing global warming.

Although Teitiota and his lawyers lost the case because the threat to Kiribati was not deemed to be an imminent risk, the ruling opened the door to recognition of the existence of climate refugees and the possibility of legal refugee protection.

Climate change will force tens of millions of people to leave their homes in the next decade, according to a report by the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF). And this would include many on low-lying atolls in the South Pacific.

‘Humanitarian visa’

In October 2017, New Zealand’s Climate Minister James Shaw announced that the incoming government was planning an “experimental humanitarian visa” category for Pacific Islanders forced to leave their homes. Partially inspired by the Teitiota case, it was envisaged that up to 100 people a year might settle in New Zealand under this scheme.

However, this humanitarian plan was quietly shelved because Pacific Islanders generally do not want to leave their homes. They prefer support for adaptation and mitigation for their continuing lives on ancestral land with refugee status as merely a last resort.

The Rainbow Warrior had visited Kiribati and Vanuatu on the voyage to New Zealand after the Marshall Islands mission. Crew members saw at first hand some of the climate pressures already apparent back then.

Cancer sufferers seeking nuclear compensation from the French government under the controversial Morin law received a boost last month when a man who had developed bladder cancer as a result of the nuclear tests was awarded almost US$180,000 by the administrative court.

This news was welcomed by both health advocates and activists.

According to the local news service Tahiti-Infos, an earlier application for compensation had been turned down by the authority dealing with the case.

The compensation law has been tightened up again after being earlier relaxed with most claims being rejected between 2010 and 2017.

Uproar in Tahiti

In May, there was an uproar in Tahiti when the French National Assembly attempted to include a clause about compensation over nuclear weapons testing into generic covid-19 legislation while the French Polynesian representatives were absent from the chamber because of the pandemic travel bans.

Tahiti’s Moetai Brotherson, one of the two French Polynesian representatives, described this move as a “scandal” and two nuclear test veteran advocacy groups, Moruroa e Tatou and Association 193, were also angry, reports RNZ Pacific.

During the three decades of French tests, the early atmospheric explosions had dusted atolls and islets with radioactive fallout.

Brotherson expressed disappointment that the French state had demonstrated yet again that it “detested” the Tahitian people. Moruroa e Tatou’s Hiro Tefaarere said he was “outraged” but not surprised because all French presidents from de Gaulle to Macron “couldn’t care less” about Polynesians.

During 2019, the French Polynesian social security agency CPS reported that it had spent US$770 million on health care costs for radiation-induced illnesses. The CPS, responsible for medical expenses and pension payments, has struggled with its budgets and wants France to take responsibility for compensation.

However, French authorities do not accept liability for test-related illnesses, claiming the nuclear blasts were “clean” unlike the earlier US and British tests in the Pacific.

The nuclear tests have rarely been an issue outside French Polynesia and independent Pacific nations. But some consciences are occasionally pricked.

A French Watergate?

Five years ago, the unmasked French bomber who sank the Rainbow Warrior in 1985 made some revealing comments during his interviews with the investigative website Mediapart and TVNZ’s Sunday programme, none more telling than that “the first bomb was too powerful, it should have ended as a Watergate” for French President François Mitterrand.

Mitterrand stayed in office for 14 years – a decade after the bombing and before he finally stepped down when his second presidential term ended in May 1995, the year before nuclear tests ended.

The bomber, retired colonel Jean-Luc Kister, added that had Operation Satanique – the sabotage plot – involved the United States, “more heads would have rolled”.

However, while the “innocent death” of Portuguese-born Dutch photographer Fernando Pereira has clearly played on his conscience for all these years, Kister’s sincere apology wasn’t without a hint of trying to rewrite history.

The claim that the secret sabotage operation never meant to kill anybody is unconvincing for anybody on board the Rainbow Warrior on that tragic night when New Zealand lost its political innocence and the crew lost a dear friend.

In 2005, two decades after the bombing and nine years after Mitterrand’s death, Le Monde published a leaked document revealing that the late president had personally approved the sinking of the ship.

The newspaper obtained a handwritten account of the operation, written in 1986 by Pierre Lacoste, who was sacked as head of the secret services.

‘Neutralise’ the Warrior

He had testified that he had asked President Mitterrand for permission to “neutralise” the Rainbow Warrior at a meeting two months before the attack and would never have gone ahead without the president’s authorisation.

The so-called nuclear “war” in the Pacific dates back to the US bombing of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki in 1945. The bombing was followed by atmospheric nuclear testing by the United States in the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1958, arguably the “dirtiest” nuclear testing.

The first so-called nuclear refugees in the Pacific were the Bikini atoll islanders who were relocated into “exile” for the first US weapons tests in 1946.

Then came the British tests at Christmas Island (now Kiribati) and in the Australian outback; the start of the French testing at Moruroa in 1966; more US tests at Johnston Atoll in the early 1960s; flight testing of ICBMs, anti-satellite weapons; and more recently “Star Wars” technology at the Kwajalein Missile Range in the Marshall Islands.

As the late Steve Sawyer, Greenpeace campaign coordinator on board the Rainbow Warrior and whose birthday was being celebrated on board the night of the bombing, noted, “the displacement of local populations and adverse health effects as a result of these programmes has not been without opposition.

“But that opposition has been so scattered and unorganised until recently that it has been little felt in Washington and Paris.”

And the Rainbow Warrior Pacific voyage was planned to make a global difference. It did, but one that shook the world and ended in tragedy.