Covering conflicts in various parts of Asia during the 1990s, many of us were “parachutists”. We dropped in, filed our stories and flew out. We were “war correspondents”. We behaved like the soldiers we covered, thronging to bars and talked in military jargon. We rushed to the sites of the latest battle, or walked into the bush to interview insurgent leaders, staying only long enough to get a couple of good quotes. We memorised the names of the hardware of war, we were infatuated with the killing machines. We chronicled the carnage. In 1996, when I returned to Nepal after covering conflicts in Sri Lanka, the Philippines and elsewhere the last thing I had expected was to have to report on a conflict in my own country. The Maoist rebels had just launched their armed struggle against the Nepali monarchy. Suddenly, this was not someone else’s war anymore – it was happening in my own country, in my own society. My own people were killing each other.

In 1996, when I returned to Nepal after covering conflicts in Sri Lanka, the Philippines and elsewhere the last thing I had expected was to have to report on a conflict in my own country. The Maoist rebels had just launched their armed struggle against the Nepali monarchy. Suddenly, this was not someone else’s war anymore – it was happening in my own country, in my own society. My own people were killing each other.

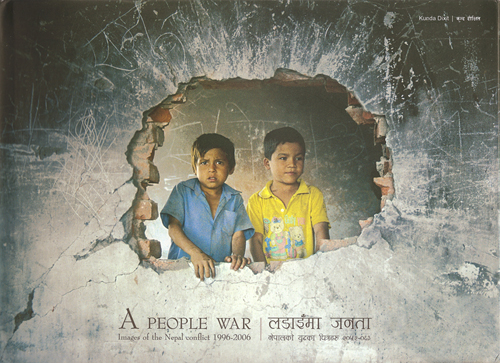

Journalism schools teach us to be observers, not to get too involved, to keep a distance. But, back home, you couldn’t be just a spectator anymore. We had to examine our own role as journalists. Did our reporting perpetuate conflict or was it going to help restore peace? We had to look beyond the battles, to how the war was affecting ordinary people. We had to investigate its human cost, expose those who benefited from conflict.

Full text of speech

Dixit, Kunda (2010). Real journalism in a virtual world. Keynote speech delivered at the Media, Investigative Journalism and Technology Conference at AUT University, Auckland, Aotearoa/New Zealand, 4-5 December 2010. Publication due in the Conference Proceedings and Pacific Journalism Review research journal, Vol 17 (1), May 2011.