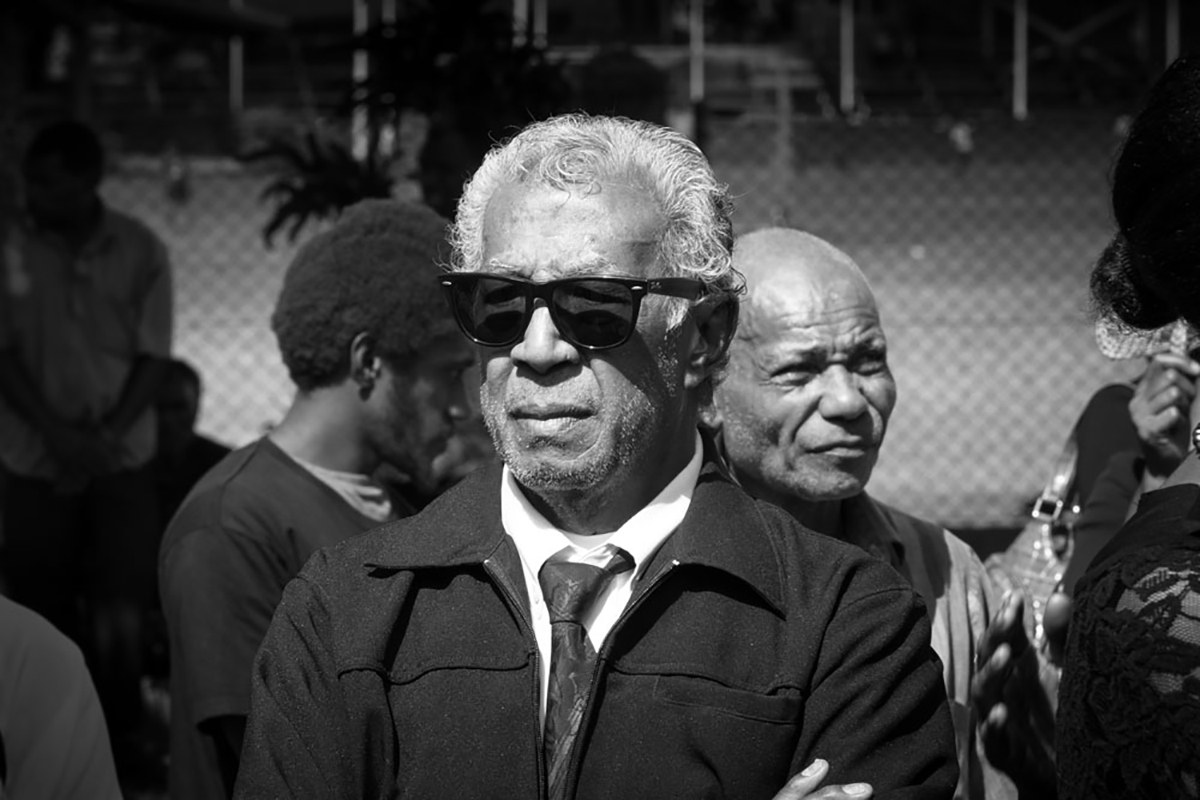

Andy Ayamiseba died a few days ago. While the West Papuan was loved, admired and supported in Vanuatu, he fought tirelessly to win a home he could return to. He died before the dream was achieved.

Originally published by the Pacific Institute of Public Policy (PIPP), this 2013 profile of Andy Ayamiseba’s life of activism in exile by Dan McGarry is one of the few narratives of the compelling story of the Black Brothers and their seminal role the formulation of a modern Melanesian identity, and in keeping the West Papuan independence movement alive in Melanesia. It has been edited to reflect recent events and republished with permission from Griffith Asia Institute’s Pacific Outlook.

PORT VILA (Pacific Outlook/Asia Pacific Report/Pacific Media Watch): In 1983, Andy Ayamiseba and the rest of the Black Brothers band descended from their flight to Port Vila’s Bauerfield airport, to be greeted by the entire cabinet of the newly fledged government of Vanuatu. They were, by Melanesian standards, superstars.

They had come to assist Father Walter Lini’s Vanua’ku Pati in its first re-election campaign, and to pass on the message of freedom for West Papua. So began a relationship that would span a lifetime of activism, a liberation dream long deferred, and ultimately, a first glimmer of hope for political legitimacy for the West Papuan liberation movement.

The Black Brothers were already widely known and loved in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. Touring PNG in the late 1970s, the band members first met Vanuatu independence figures, including Hilda Lini, Kalkot Mataskelekele and Silas Hakwa.

READ MORE: Benny Wenda’s tribute

Students at the University of Papua New Guinea at the time, they returned to Vanuatu to play key roles in Vanuatu’s move to independence.