Media practitioners and educators from around the region gathered at the University of the South Pacific last week to discuss issues about the role of the media in relation to democracy in the Pacific. Wide-ranging topics such as deliberative journalism, critical development journalism and peace journalism were debated. Here a former USP head of journalism, Professor David Robie, now director of AUT University’s Pacific Media Centre in New Zealand, outlines some of the ideas and why global journalists are talking them seriously.

ANALYSIS: South Pacific media face a challenge of developing forms of journalism that contribute to the national ethos by mobilising passive communities into seeking change.

Instead of clinging to only news values that have often led international media to exclude a range of perspectives, a rethink is needed that would promote “deliberation” by journalists to enable the participation of all community stakeholders.

Critical deliberative journalism is issue-based and includes diverse and even unpopular views about the community good and encourages an expression of plurality.

In a Pacific context, this resonates more with news media in some developed countries that have a free but conflicted press such as in India, Indonesia and the Philippines. This has far more relevance in the Pacific than a monocultural “Western” news model as typified by the Australia and New Zealand media.

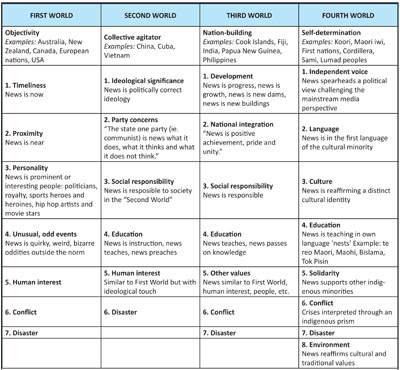

Early in the millennium, I examined notions of the Fourth Estate in the South Pacific. These were applied through a “Four Worlds” news values prism that included the status of indigenous minorities in dominant nation states.

This journalism model has been widely used over the past decade in the Pacific and many of my graduates working in key news media posts all over the world have used it as a tool.

Globalisation and critical development journalism

Development should lead to human progress, but this isn’t always the case. Journalists are a “crucial link in the feedback loop”, ensuring that improvements in the quality of life can be sustained and don’t permanently damage nature and the human environment. Authors such as one-time Inter Press Service bureau chief in Manila, Kunda Dixit, have warned against the cost of globalisation for developing countries of the global South, such as in the Pacific.

Authors such as one-time Inter Press Service bureau chief in Manila, Kunda Dixit, have warned against the cost of globalisation for developing countries of the global South, such as in the Pacific.

He calls this rapacious process sweeping the world today “gobble-isation”, and says “there is a danger that free trade will worsen the balance of payments deficits, accumulate debts, and force poor countries to set things right by accelerated exploitation of their forests, marine and mineral resources”.

According to Dixit in his classic book Dateline Earth: Journalism as if the planet mattered (republished as a new edition in 2010, which every aspiring Pacific journalist should read), this ‘massive haemorrhaging of wealth has already bled many countries dry’ and ruined their environment.

“In addition, languages, indigenous cultures, oral testimony are vanishing forever, obliterated by a ‘monoculture’ spread by the globalisation of the economy and communications,” Dixit says.

“The more tangible signs of crises are alarms over ozone depletion, global warming, rainforest loss and fishless seas—the results of the dizzying acceleration of human technological advancement in the past century. It is called ‘development’, but where is it taking us?”

If journalists are serious about tackling the major issues confronting the Pacific such as climate change, exploitation of the forests and mines, and depletion of the fisheries, they will need to study the theory and practice of their profession far more critically.

Receptive to new ideas

They need to be far more receptive about new ideas and being non-conformist. The reluctance to study other journalism models is one of the reasons Fiji journalism hasn’t progressed very far over the past decade.

“Traditional journalism schools teach you to look for the counterpoint to make stories interesting. They tell you that it is the controversy, the disagreement, which gives the story its tension,” says Dixit.

“Most reportage then sounds like a quarrel, opposites pitted against each other, even when the point of argument may be minor and the two sides are in overall agreement.”

Corporate and mainstream journalism often “provides technically accurate but kneejerk reports” about dramatic events or issues, says Angela Romano in her recent book on international models.

The book, International Journalism and Democracy, argues for a “more sophisticated” understanding by journalists of the consequences of their work.

Unfolding trends and issues

It also offers a strong case about the role of deliberative journalism in a democracy, which encourages “greater consideration of the subtle nuances of the visible facts” and how seemingly obscure details make up a more rounded and greater picture of unfolding trends and issues.

As a philosophy, deliberative journalism involves some “subjectivity”, but in a sense it is more objective than mainstream reporting when it is “attached to the process of democratic deliberation”.

It involves robust reporting and analysis of public issues rather than focusing on any particular “side” or outcome.

Deliberative journalism involves reporting the daily news as issues rather than as events. It also requires a reflection on how high standards of objectivity might be balanced with fairness and ethical considerations.

Deliberative journalism involves empowerment, often a subversive concept in conservative societies.

It involves providing information that enables people to make choices for change. Deliberative models include notions such as public journalism, development journalism, peace journalism and even human rights journalism.

Development journalism in a nutshell

Development journalism in a nutshell is about going beyond the “who, what, when, where” of basic inverted pyramid journalism; it is usually more concerned with the “how, why” and “what now” questions addressed by journalists.

Some simply describe it as “good journalism” with greater context.

As a media model, development journalism peaked at the height of the UNESCO debates for a New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO) in the 1970s.

The debates were used by Third World countries to argue for a more positive portrayal of developing countries by Western news organisations such as Associated Press (AP), United Press International (UPI) of the United States, France’s Agence France-Presse and Reuters of the United Kingdom.

Development journalism was understood and linked by Western journalists to a “biased” reporting approach focused on positive developments as opposed to the “conventional focus on conflict, such as failed government projects and policies”, argues an Australian-based Malaysian authority on the topic, Dr Eric Loo.

However, both Loo and I actually call for an investigative, or critical development journalism, which focuses on the condition of developing nations and ways of improving this.

Proposed government projects are put under the spotlight and they are analysed to see whether they really would help communities.

People are usually at the centre of these issue-based stories. And often the journalist uses compelling storytelling to come up with proposed solutions and actions.

Deliberative journalism also means a tougher scrutiny of the region’s institutions and dynamics of governance. Answers are needed for the questions: Why, how and what now?

Journalists need to become part of the solution rather than being part of the problem.

An extract from the paper "'Four Worlds' news values revisited: A deliberative paradigm for Pacific media" presented at the Media and Democracy in the South Pacific conference at the University of the South Pacific on 5 September 2012.

This article as it appeared in The Fiji Times on 13 September 2012.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand Licence.

MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY

Conference at USP, 5/6 September 2012

'Leeway' in decree, says Sun deputy editor

More iTaukei dailies needed, says linguist

Opinion - Rumblings at the Edgefest

Wansolwara special reports on media and democracy

Social media the news medium of the future in Pacific

Journalists told 'be part of solution'

Fiji journalists urged to take advantage of lifting of censorship

Wrap-up on the conference issues

Debate about Pacific journalism