COMMENTARY: The 26th anniversary of the first 1987 Coup has revived some traumatic memories for many of us who lived through it – the shock, the air of menace, the violence, the feeling that Fiji would never be the same again.

Tens of thousands of our best and smartest people simply decided there and then that there was no future for themselves and their families and packed up and left. The exodus was so dramatic that it soon altered the entire racial balance in Fiji.

The Indo-Fijians – or Indians as they were then called – were once in the majority. But so many of them fled to New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the US that the “Fijians” – as the i’Taukei were then known – gained the ascendancy and remain the dominant racial grouping.

You really have to be in your mid-thirties, at least, to recall the events of that life-changing day, which means that to the overwhelming majority of contemporary Fijians, May 14, 1987, is a date in the history books, not something they experienced.

Yet more than ever, it’s important for every Fijian to appreciate the magnitude of the schism that ripped apart the social and political fabric of the nation. Racial supremacy in favour of the i’Taukei was imposed at the point of a gun even though they had no cause whatsoever – as the dominant landowners – to feel in the least bit threatened by the other communities.

It produced a crude form of minority rule in Fiji in which the members of other races became second-class citizens.

And worse, it led to hideous excesses, as far too many i’Taukei turned on their fellow citizens, snubbing them, beating them and robbing them in a disgraceful display of greed and stupidity.

Arrogant superiority

That sense of arrogant superiority – of surly self-entitlement – lingered on and was again a feature of the second coup in 1987, triggered the events of 2000 – the disastrous Speight coup – and persisted through the Qarase years until 2006, when one indigenous leader in the form of Voreqe Bainimarama declared that enough was enough.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the events of May 14, 1987 triggered the most disastrous era in Fijian history – three decades of instability that deprived the country of three decades of progress.

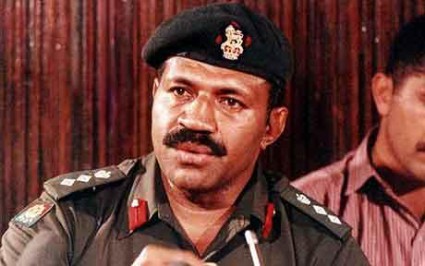

I, for one, am continually bemused by the way in which the man ostensibly responsible – Sitiveni Rabuka – is lionised simply because he was eventually able to gain a degree of respectability by morphing into an elected leader.

Rabuka is continually being invited to international conferences – most recently in Australia and before that New Zealand – as a kind of eminence grise or eminent person to comment on political events in Fiji.

Indeed, he is again taking centre stage tonight at a panel discussion at the University of the South Pacific on the processes leading up to next year’s election.

Now, Rabuka is a pleasant enough character to meet, still retains a semblance of the good looks and bearing that made him a 1980s heart-throb and carries a definite aura of celebrity as a living, breathing relic of one of the most tumultuous periods of our history.

Yet am I alone in being astonished that those who scream the most loudly for an immediate return to democracy nowadays seem to be the first to scramble to share a platform with him?

Triggered earthquake

Surely this is the man who started it all, who triggered the earthquake, who carries more blame than anyone else for Fiji’s lost decades?

Yes, he has begun to say a tentative “sorry”, to tell the world that it was a mistake. Yet there’s a decided absence of overt shame on Rabuka’s part that so many lives were destroyed, so many families uprooted, so many opportunities lost.

There was a particular element of cruelty in the choice of the date of the coup – the anniversary of the arrival of the Girmit, the first Indian indentured labourers brought to Fiji by the British. For many Indo-Fijians, the events of May 14 have left an indelible scar.

I met Sitiveni Rabuka for the first time during the events of 1987 when we covered the coup for Australia’s Nine Network. He was the picture of civility yet it all belied the menace he’d displayed to get his own way.

Fiji’s current ambassador to the United Nations, Peter Thomson, was then Permanent Secretary for Information. He tells of how Rabuka came into his office wielding a pistol and forced Thomson to write the public announcement of the coup.

In those days, there was no television, only Radio Fiji. And the words that Rabuka uttered in his radio broadcast are etched in my memory to this day: “At 10 o’clock this morning, troops of the Royal Fiji Military Forces took over the Government of Fiji and neutralised Parliament…”

He had also taken the Dr Bavadra government hostage and, in doing so, changed the course of Fijian history forever.

Many memories

In my own mind’s eye, there are so many memories of the following days, all of them extremely confronting for someone who had grown up in Fiji believing in the multiracial ideal.

I was at Channel Nine in Sydney working when the coup was announced and immediately went on Ray Martin’s talk show to provide some of the background before racing to the airport via my flat to pack a small suitcase and pick up my Fiji passport.

The plan was for me to go into Suva without a film crew and avoid the hotels just in case the overseas media could not get in or happened to be thrown out. I stayed with a friend – a prominent lawyer – who remains a friend to this day, not least because he came to my aid when I wasn’t as smart as I thought I was and got arrested anyway when I was stupid enough to be caught in a taxi with a couple of other journalists.

I was taken by armed troops to the Central Police Station, where my Fiji passport became an immediate problem.

“Who are you? What are you doing with this? Where are you staying?” It occurred to me that my interrogators thought I was a foreign spy.

But what really agitated them were some stamps in my passport in Arabic. It was at the time of the big 1980s Libyan scare in the Pacific that arose from Colonel Gaddafi’s flirtation with Vanuatu.

“You been in Libya? Are you working for Libya?” “No I was born in Fiji and I work for Channel Nine”.

Eternal credit

To his eternal credit, my Indo-Fijian lawyer host suddenly arrived at police HQ and eventually secured my release. So my own detention of several hours was far less traumatic than those of others, who in some cases were held for days and severely beaten.

Never before or since has been tagged as a Methodist luve ni talatala (child of a clergyman ) come in quite so handy in Fiji. Yet never before had I been so ashamed of the actions of the Methodist Church.

The coup was not only supported by some of the Church hierarchy, it was accompanied by Sunday bans – instigated at the urging of certain Methodist talatalas – that saw Christians and those of other faiths harassed at road blocks and even driven from beaches at gunpoint for “breaching the Sabbath”.

All around Suva were stories of the less fortunate – those either targeted because of their political activities, especially in the case of Bavadra government staffers, or merely because of the colour of their skin.

To me, this was the most heartbreaking aspect of all; when “The Way the World Should be” – as the visiting Pope John Paul had described Fiji just months before – became a racist hellhole.

I can still feel the anger to this day – the utter disgust of watching helplessly while well-dressed Indo-Fijian passersby were beaten by a rampaging i’Taukei mob in the car park of the Holiday Inn, then the Suva Travelodge.

Those pictures are still the most obscene ever recorded in Fiji. But they were only the most visible manifestation of the widespread violence that was visited on Indo-Fijians in a series of sporadic attacks – some organised, some random and opportunistic.

Blind eye

To their eternal shame, the RFMF and police often turned a blind eye even to events that unfolded virtually in front of them. Marauding youths threatened to cook coup dissenters like Richard Naidu – the lawyer and then Press Secretary to the deposed Prime Minister – in a lovo they’d dug in front of Ratu Sukuna’s statue at Government Buildings.

It was a time of terror and of hatred. Even if you escaped a beating or a home invasion, you could still be elbowed off the footpath into the street, as an i’Taukei thug did to me And it was repeated all over again later in the year in Coup 2 – as it became known – and on an even bigger and more sinister scale in the Speight coup of 2000.

Only now – more than a quarter of a century later – has the cycle been broken. And, ironically, it’s thanks to a revolution – also at the point of a gun – in which racial equality and genuine democracy is being imposed and a new order created.

The Bainimarama Revolution is easily the most important point in Fiji’s history since 1987, with its promise of finally breaking the nation’s coup culture by dissolving race as the defining factor in national life.

Yes, many people still think Voreqe Bainimarama is on a quixotic mission that cannot possibly succeed. One of his principal political opponents, Ro Teimumu Kepa, has said that race is a fact of life in Fiji and warned last year of the prospect of “racial calamity”.

Yet by even attempting to forge a common national identity by declaring everyone “Fijian”, Commodore Bainimarama has established himself – in my view – as the boldest and bravest of our leaders since independence.

If he fails, the overwhelming odds are that Fiji will regress and the notion of forging a successful multiracial nation will be lost. But if he succeeds, nothing can stop Fiji from cementing its place as the pre-eminent Pacific nation and reaching greater heights.

Social revolutionary

How did we come to this view of Bainimarama as social revolutionary rather than self-interested coup maker, a depiction that invariably has Bainimarama’s critics seething? Because someone had to break the never-ending destructive cycle of racial politics in Fiji and he alone has had the foresight and fortitude to do so.

Bainimarama may not be the first Fijian leader to try to break through the communal barrier. Dr Timoci Bavadra tried to do so in 1987 but lasted only a month.

But there’s no doubt that every other political leader – from Ratu Mara through to Laisenia Qarase – owed their fortunes and allegiances to one racial grouping, however successful they might have been at forging occasional multiracial coalitions.

What singles Bainimarama out from the pack is that he will go to the nation next year asking every Fijian to support his quest for a new Fiji, a non-racial Fiji in which all Fijians – irrespective of race and religion – will be invited to share his vision.

I sat around a couple of days ago over coffee reminiscing about the bad old days with a couple of friends, including the lawyer who rescued me from military/police custody 26 years ago this week.

We don’t agree on everything but there’s one thing we did agree on; that life in the new Fiji is so much better for everyone than the old. The fear and trepidation has gone, replaced by optimism and hope.

This article was first published on the blog Grubsheet