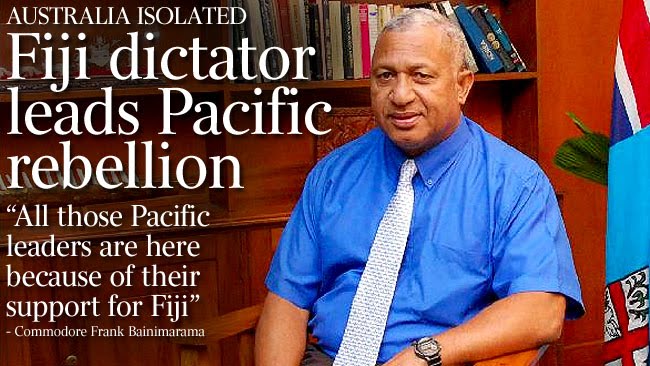

SUVA: Australia and New Zealand are locked in a stand-off with Fiji’s military strongman Commodore Frank Bainimarama over his refusal to bring back democracy after four coups in two decades.

Sanctions and other tough measures by Canberra and Wellington against the regime have been matched by a round of diplomatic expulsions by the South Pacific nation, which in turn is looking more and more to China for aid and support.

Can this policy of isolating and punishing Fiji work?

The chairman of the US Congress Foreign Affairs Sub-committee on Asia and the Pacific, Eni Faleomavaega (from neighboring America Samoa), is not convinced and sees "bad developments" arising.

"Of course, we don’t agree with Fiji not having a democratic government. But we have to appreciate and understand the complexities facing Fiji,” he told the Samoa Observer recently.

Fiji is indeed complex. Australian National University historian Professor Brij Lal describes it as “a bit like Churchill's Russia: a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.”

A multi-ethnic nation of more than 945,000 people, Fiji was a British Crown colony for 96 years before independence in 1970.

According to the 2007 census, indigenous Fijians make up 57.3 per cent of the population.

Low birth rates

Ethnic Indians are descended mostly from imported laborers who worked on colonial sugar plantations. They are now 37.6 per cent of the population and their numbers are dropping, thanks to migration and low birth rates.

Europeans, Chinese and other Pacific Islanders make up the rest of the population.

After independence, Fiji enjoyed a measure of stability under the firm grip of founding Prime Minister, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, a high chief.

But when Mara’s Alliance Party lost power to a multi-ethnic Fiji Labour-National Federation Party coalition in 1987, Fijian nationalists took to the streets, claiming Indians had seized control of the country.

Military strongman Sitiveni Rabuka executed a coup—the first in the South Pacific. The new government was ousted before it completed a month in office.

A second coup followed soon after.

Democracy and reconciliation returned eventually and in 1999 Rabuka lost government to the Labour Party Coalition. When Labour Party leader Mahendra Chaudhry emerged as Fiji’s first Indian prime minister, it was déjà vu for Fijian hardliners.

Indigenous rights

A hitherto unknown businessman, George Speight, took up the indigenous rights cudgel. With a handful of renegade soldiers, he stormed Parliament and captured Chaudhry, and his government.

The ensuing hostage crisis lasted 52 days until Speight’s gang was captured and jailed by military commander Bainimarama, who appointed Laisenia Qarase as the caretaker prime minister.

Democracy returned and Qarase won elections in 2001 and 2006. Emboldened by his second victory, Qarase revealed plans to pardon the

coup makers.

Bainimarama, who narrowly escaped an assassination attempt by Speight sympathisers during a failed army mutiny in November 2000, reacted angrily and removed Qarase.

Military rule under Bainimarama belies Fiji’s marketing image as a balmy tourist paradise. Both sides of the racial divide feel marginalised: indigenous Fijians economically, ethnic Indians politically.

Each group blames the other for its problems, but Bainimarama instead points to a past of bad governance, corruption and devious politicians playing the race card to gain power.

Rivalries within the indigenous population have also muddied the waters.

Speight allegedly did not just stage a coup just to remove an Indian prime minister. He has been accused of acting on behalf of some Kubuna Confederacy chiefs against then president (and former prime minister) Ratu Mara, a chief of the Tovata Confederacy.

Ratu Mara was the country's president at the time of the 2000 coup.

Conspiracy theories

The 2006 coup spawned similar conspiracy theories. Bainimarama, it is alleged, is a front for the rejuvenation of the Mara and Ganilau dynasties. But Bainimarama says he acted to remove a “corrupt, racist” government. His agenda, he says, is to rebuild “a non-racial, culturally vibrant, truly democratic nation."

Australia and New Zealand are refusing to swallow this line and instead demand Bainimarama make good his pledge to conduct free and fair elections.

When in 2009 Bainimarama postponed elections to 2014, Australia and New Zealand lashed out with sanctions and renewed attempts to isolate Fiji.

They fear the longer a military government stays in power, the higher the risk of violence. Moreover, they worry a “coup culture” could take hold in other island states.

Sanctions and diplomatic isolation have had little real impact. While banned from the Commonwealth and the Pacific Islands Forum, Fiji continues to enjoy ties with countries like China, India, and Korea, to name a few.

Chinese aid to Fiji reportedly stands at $150 million (a tai-chi expert is apparently part of the package—he will be sent to Fiji to encourage “positive thinking”).

At the World Expo in Shanghai in August, Bainimarama lauded China as a “true friend” which had shown “understanding,” "assistance,” and "true wisdom."

Tough times

China’s civil affairs minister Li Guo responded in kind, saying: “Our relationship has stood through tough times in the last 35 years.”

In an interview with the news organisation Agence France-Presse, Bainimarama described China as "the only nation that can help assist Fiji in its reforms because they think outside the box.”

While Fiji and China warm up to one another, Australia's Acting High Commissioner, Sarah Roberts, has been expelled from Suva in retaliation for alleged Australian sabotage of a Melanesian countries’ meeting in Fiji.

Fiji hastily organised an 'Engaging the Pacific' meeting to replace an abandoned Melanesian Spearhead Group meeting. Ten island countries showed up in apparent support for Bainimarama. Some island leaders have had their own runs-ins with Australia and New Zealand and like how Fiji has stood up to these big regional governments.

At the Pacific Islands Forum meeting a week later in Vanuatu, the leaders of three countries (Papua New Guinea, Kiribati and Tuvalu) who attended the Engaging Pacific meeting, stayed away.

While Australia claims the leaders' absence did not reflect support for undemocratic Fiji, a leading Fiji-born academic disagrees. Dr Steven Ratuva, who teaches in Auckland University's Centre for Pacific Studies, says a new approach is needed.

Is it time to rethink how to deal with Fiji?

The bottom line is this: Fiji has major problems. Around 42 per cent of its people live on or below the poverty line.

A shantytown population is more than a 100,000. Unemployment is leading to increasing crime. People are crying for relief.

It is time for the leaders to act. - 7010 Asia Society Online/Pacific Media Watch