OPINION: By Glenn Fredly

JAKARTA (Asia Pacific Report/Jakarta Post/Pacific Media Watch): The remarks of renowned American philosopher John Dewey, “If you want to establish some conception of a society, go find out who is in jail”, has been quoted many times to elaborate on the state of freedom in many parts of the world, including Indonesia.

Indeed, reports about people being imprisoned, tortured or executed because of their views or faith are rife in the country.

Looking closely at prisons in Indonesia today, at least 20 people have been locked up for peacefully expressing their views about religion and politics, according to Amnesty International.

Eleven of them were charged with “blasphemy or defamation of religion” and the rest were peaceful pro-independence political activists.

Papua would probably quickly pop up in our minds when talking about the province with the highest number of imprisoned peaceful political activists. Indeed the easternmost province is home to an active armed pro-independence movement.

In western Indonesia, such “insurgence” ended after the government secured a peace agreement with the Free Aceh Movement in 2005.

List of punishers

However, Amnesty International has also identified the underdeveloped province of Maluku, which currently has no record of an armed pro-independence movement, on top of the list of punishers of peaceful political activists.

Eight people from Maluku are serving prison sentences for what the government calls makar (treason). They are Johan Teterissa, Ruben Saiya, Johanis Saiya, Jordan Saiya, John Markus, Romanus Batseran, Jonathan Riry and Pieter Yohanes.

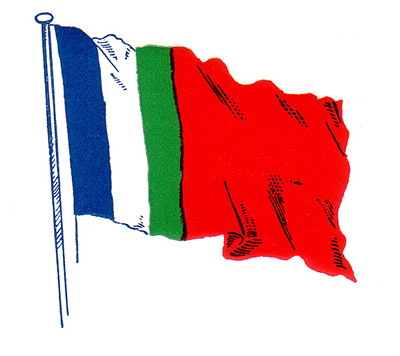

The Benang Raja flag of Maluku … outlawed. Image: File

Their only offence is unfurling the Benang Raja flag, a symbol of the aspiration for Maluku’s independence, on June 29, 2007.

Johan Teterissa was leading a group of 22 activists who performed the traditional war dance cakalele in front of then-president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono in the Maluku capital of Ambon, before they were all arrested for unfurling the flag.

If Indonesia respects rights to freedom of expression, they should not spend a single day in prison for such peaceful activity. Yet they were thrown behind bars for between 15 and 20 years. Johan was among those denied medical care while at least four of the activists have died in prison.

The Morning Star flag of West Papua … outlawed. Image: SIBC

Amnesty International considers Johan and all those arrested like him prisoners of conscience, who are jailed for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression and assembly. Their arrests highlight the police’s failure to respect these rights.

Adding insult to injury, in March 2009, Johan and dozens of prisoners of conscience were transferred to prisons in Java, more than 2,500 kilometers away from their home. The isolation meant family visits were almost impossible, which is unnecessary, costly and cruel on prisoners and their families.

Maximum security prison

On November 28, 2016, I had a chance to visit Johan Teterissa at a maximum security prison in Nusakambangan, Central Java, with the help of Amnesty International and the Jakarta Legal Aid Institute as part of a campaign to release all prisoners of conscience in Indonesia.

As a Maluku native, I have been enjoying the fruits of freedom in Indonesia after the fall of Suharto in 1998 through my work as an artist. I have been able to freely express my thoughts through songs peacefully, but many in Maluku like Johan and other activists still lack this basic right to freely express political aspiration.

This is why I am calling on the government to release Johan and his friends and grant them amnesty.

Johan and his friends posed no threats to the president when unfurling the “forbidden” flag, but the government at that time considered the act treason. Their arrests clearly tarnish Indonesia’s image as a free country.

The administration of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo must correct this mistake to restore Indonesia?s so-called freedoms.

Differences in political views must be clearly respected and expressing it peacefully in public never constitutes a crime. There was recent progress when all the prisoners from Maluku were transferred to a prison in the province, enabling easier access to visits for their families.

The transfer also means the administration is open enough to respect different political views.

Amnesty needed

However, relocating them to a Maluku prison is not enough. They must be granted amnesty. Through amnesty, the Jokowi administration could restore Indonesia’s image as a country where anyone can easily express their ideas freely through peaceful means without fearing criminal charges.

In early 2015, I had an opportunity to meet President Jokowi with other artists. I personally asked the President about the fate of political prisoners from Maluku and Papua. I was happy with his firm answer that he would free all political prisoners as soon as possible.

Shortly after, President Jokowi released and granted clemency to six Papuan political prisoners.

I am sure the transfer of the Maluku political activists is part of his plan to release and grant them amnesty. By doing so the President will rebuild trust and public confidence in the eastern part of Indonesia in the government.

I personally believe the peaceful call for independence derives from political frustration among activists in Maluku. One important fact is that Aboru, the village where Johan and other Maluku activists are from, is still very much underdeveloped and neglected by the central and local government.

The government must tackle the root causes instead of arresting them for peacefully expressing their political aspirations. The President must understand this background, so he would be convinced that granting amnesty is the right course of action to solve this case.

I am confident that President Jokowi will walk his talk to release and grant amnesty to all political prisoners in Papua and Maluku in the near future. So when he is asked “who is in jail?? he can confidently say Indonesia no longer has political prisoners there.

Glenn Fredly is a musician and campaigner for freedom of expression. This article was first published in The Jakarta Post.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3