Twenty-one years ago, I wrote a book about indigenous independence and nationalist struggles in the South Pacific. The British publishers wanted a “paradise lost” cover of a beach fringed with coconut palms. It was the opposite of the book’s intended message.

The publishers reluctantly changed the design before printing, coming up with an insipid flag cover to better reflect the title, Blood on Their Banner. It was, however, the wrong flag—depicting the ensign of Vanuatu instead of the Kanak banner portraying the sacrifice that inspired the title.

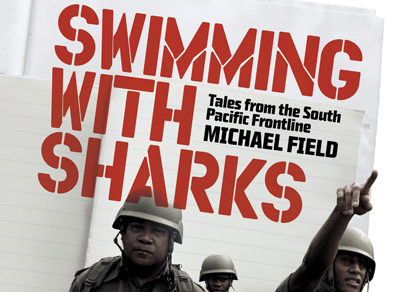

Michael Field’s book has a similar obligatory palm-skirted beach, albeit relegated to the back cover. Again the image is far-removed from his central theme. But at least one of Field’s photographs of Fiji coupster soldiers fronts the book: after all, many of his title’s Pacific caricature “sharks” reside in Suva.

Swimming with Sharks: Tales from the South Pacific Frontline gives a somewhat cynical, gloomy and depressing series of snapshots of the region. It is heavily populated with carpetbaggers, conmen, corrupt and self-interested politicos, opportunists, religious fundamentalists, coup-prone soldiers (not just in Fiji) and other sordid characters.

But his sombre tales are spiced with humour, irony and engaging anecdotes. And beneath the amusing cynicism is a deep commitment to the Pacific that has spanned more than three decades.

Field has developed an extraordinary penchant for getting up the noses of paranoid and vindictive island authorities, making him persona non grata in Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru and Tonga.

His run-ins with authority kicked off in Samoa, where he began his Pacific love-hate affair in the 1970s as a VSA volunteer, has family kinship ties—and was dumped by the state-owned Savali “official” newspaper. Field was editor, reporter and photographer at the time. He wanted to publish a story on electoral corruption but then prime minister Tupuola Efi wouldn’t have a bar of it.

“I had to pull the story, but put nothing in its space other than a small note saying Tupuola had removed its content. ‘Leave in 24 hours,’ they said. Six weeks on, with a memorable party, I departed.”

Inspired by his time in Samoa, Field penned Mau: Samoa’s Struggle Against New Zealand Oppression, a 1984 book that lifted the lid on the unsavoury Kiwi colonial past in Samoa—and contributed eventually to a national apology to Samoans by New Zealand’s then Prime Minister, Helen Clark, in 2002.

Field’s brushes with other Pacific governments and regimes have been more arbitrary, but effectively restrict a journalist with considerable influence in a dwindling pool of New Zealand news people keeping the public informed about the region.

In the case of Nauru, he got offside with René Harris— “perhaps the most corrupt of all Nauru’s leaders”—and was banned in 2001, apparently because of unwelcome publicity over the country’s shady offshore banking operation and the Russian Mafia. The ban was also allegedly in support of Kiribati, which had earlier declared Field “undesirable” because of an environmental expose: “I wrote a feature for Pacific Islands Monthly about excrement-covered beaches."

While President Tebaroro Tito had “cited the toilet story”, Field suggests the real reason was linked to his reporting over a Chinese satellite tracking station on the eastern end of Tarawa. Tito lost the ensuing elections and incoming President Anote Tong closed the base and switched diplomatic horses, substituting Chinese aid with Taiwanese.

In the case of Tonga, Field laments that he irritated the kingdom because he made the mistake of “taking them seriously” and questioning royal governance over issues such as sale of Tongan passports to Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos and scores of Hong Kong Chinese, the “court jester” and the great millennium scam, and nuclear waste: “I spent a lot of time covering Tonga at a time when most other journalists were writing warm platitudes about the fat king [the late Taufa’ahau Tupou IV] and the crown prince [now King George Tupou V] driving a London taxi.”

Field has few kind words to say about Tonga, which he dismisses as a kingdom that is merely a “role model for the Emperor with No Clothes”.

But he reserves most of his venom for Fiji and this is where his partisanship in the region has become most pronounced and hyped to the point where his judgment is questionable.

While Field has official police and Gazette notices confirming his bans around the region, his Fiji blacklisting was far more opaque—on one occasion he was informed about this via a media conference by putsch leader Voreqe Bainimarama. A week after the abrogation of the 1997 Constitution in the so-called “fifth” coup on April 10, 2009, Bainimarama announced a relaxed policy for foreign media, adding: “We are not going to let in people that we did not allow in the first place, people like Michael Field.”

The antipathy is mutual. Field regards the dictator as a “narcissist, living a predatory lifestyle” and having a “grandiose sense of self-worth”. Bainimarama regards Field as “clueless in coup coup land”, to coin a Fiji Times headline on one of his post-Speight articles.

The book had the potential to rival Tuturani, Scott Malcolmson’s fascinating “political journey” in the Pacific. Instead, it is surprisingly simplistic, and fragmented and episodic in style—a mishmash of past story notes with little insight into many key issues. Not much for regional academics to savour. For example, Francis Ona and the background to the 10-year Bougainville civil war rates just six sentences, and there is barely a mention of Fiji’s complex and traditional indigenous confederacies, which are at the heart of the “coup culture”.

But Michael Field deserves plaudits for the way Swimming with Sharks provides testimony to his sustained coverage of the Pacific beyond the paradise metaphor and challenges a media that rarely cares.

Dr David Robie is director of the Pacific Media Centre at AUT University, Auckland. His blog is Café Pacific. This review was first published in The Walkley Magazine, October/November 2010, p. 49.

Swimming with Sharks: Tales from the South Pacific Frontline, by Michael Field, published by Penguin, Auckland, 2010, 256 pp. ISBN 979-0-14-320373-5.

Reference: Malcolmson, S. (1990). Tuturani: A political journey in the Pacific Islands. London: Hamish Hamilton.