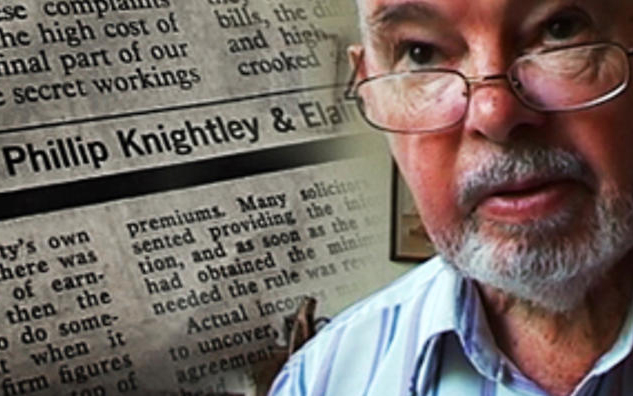

Richard Lance Keeble

LONDON (Asia Pacific Report / Ethical Space / Pacific Media Watch): Phillip Knightley, the investigative reporter who has died aged 87, was a wonderful storyteller. Once he told my students at City University (where I was a journalism lecturer from 1984 to 2003) how, when he was a rookie reporter in the late 1940s on a suburban Australian rag, the news appeared to have dried up for the next edition so his editor asked him to invent a story.

Phillip promptly wrote a “report” about a man (he dubbed him “the hook man”) who terrorised women on the local buses by lifting up their skirts with a clothes peg. So the front page splash headline: “‘Hook man’ terrorises women on the buses” duly appeared on the Friday.

Not surprisingly, Phillip worried about the response of the local cops to his invented “exclusive”. Monday passed without any call from the cops.

Then on Tuesday, he received a call from the local police station. “Is that Knightley?” the cop asked abruptly. “Yes,” he responded nervously. “Well,” the cop continued, “you know that ‘hook man’ – we’ve caught him!”

In every respect, that was a typical Phillip story: extremely funny – but was it true or false: fact or fiction? In reality, the story as well as being extremely entertaining was a device to encourage his audience to be sceptical.

Indeed, Phillip Knightley was for me the supreme journo: always sceptical, fiercely intelligent, courageous, witty, highly sociable, politically astute – as well as being a brilliant writer and storyteller.

Vast achievements

His achievements in journalism and publishing were vast: major roles in The Sunday Times’s investigations into the thalidomide scandal and Kim Philby, the British intelligence chief exposed as a Soviet spy; twice awarded the Journalist of the Year award; closely involved in the work of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists – and so on.

But his contribution to the development of journalism education in this country was substantial too. His major texts (The First Casualty, his seminal history of war reporting; The Second Oldest Profession, on spying, and his autobiography, A Hack’s Progress) are essential reading for all journalism students.

They capture the best elements of journalism: original, clear writing, the synthesis of a vast amount of often complex information, a political awareness, an immediacy; a sense of history and a fascination with the complexities of human nature.

As he wrote at the end of A Hack’s Progress: “So my advice for the new generation of journalists is to ignore the accountants, the proprietors and the conventional editors and get on with it. And your assignment is the same as mine has been – the world and the millions of fascinating people who inhabit it.’

Moreover, Phillip clearly enjoyed the contact with students and his appearances at City University and more recently at the University of Lincoln (after I became a professor there in 2003 and where Phillip was appointed a Visiting Professor) always drew big, appreciative crowds.

He was also inspirational in smaller, workshop settings, forever keen to share his knowledge of investigative techniques and his spin on various tricky ethical/political dilemmas. For instance, intriguingly, he never had a bad word to say about cheque-book journalism.

Phillip spent a lot of his career writing on the intelligence services – but he was never seduced by the lure of the secret world and very critical of the hacks who got too close to the spooks. As he wrote: “…although journalism is riddled with people working for intelligence services, I would stay clear of the game.”

In his autobiography, he concluded wryly: “The main threat to an intelligence agent comes not from the security service in the country against which he is operating but from his own centre, his own people.”

Highly managed operation

And he bravely revealed that the Philby scoop was, in fact, a highly managed operation. The Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) “knew beforehand what we were about to publish each week. The editor-in-chief of The Sunday Times, Denis Hamilton, had come to an agreement with the service.” So much for intrepid investigative reporting!

Phillip was also an activist journalist. For instance, in 1999, I organised a meeting at the Freedom Forum in London protesting at Fleet Street’s coverage of the Nato attacks on Serbia and Phillip immediately agreed to speak on a panel.

At international forums and in media articles (in both the prestigious press and alternative, progressive journals), he constantly criticised government and military moves to censor and sanitise the reporting of war – and journalists’ failure to confront the secret state effectively.

As he reflected: "I know now that the influence journalists can exercise is limited and that what we achieve is not always what we intended. It is the fight that counts."

Richard Lance Keeble is joint editor of Ethical Space: The International Journal of Communication Ethics. This obituary was first published on the Ethical Space blog and subsequently on Asia Pacific Report. Knightley’s journalism career began in Fiji.

Pacific Journalism Review of A Hack's Progress about Knightley's Fiji connection

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3