Christine Russell analyses the problems for media covering the post-Pacific tsunami nuclear power plant crisis as the emergency grows increasingly treacherous.

OPINION: The nuclear power emergency in northeast Japan grows more treacherous and uncertain, as plant operators struggle to contain escalating dangers at several nuclear reactors in hopes of preventing a disastrous release of radioactivity into the environment.

The unfolding crisis in Japan continues to draw comparisons with the world's previous nuclear power accidents. The big question is the degree to which Japan's current nuclear power emergency resembles the more contained 1979 US Three Mile Island accident, or the worst in history, the 1986 Chernobyl catastrophe in the Ukraine.

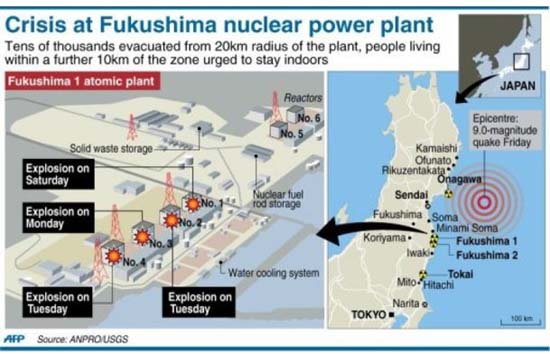

"I covered Chernobyl and I covered Three Mile Island," NBC's chief science and health correspondent Robert Bazell said today. "So far it's not anything like Chernobyl. Let's keep our fingers crossed that it will continue to stay that way." A jet-lagged Bazell, who had just arrived in Tokyo, stressed, "the situation here is still not under control." He emphasized that "it is a race against time" to prevent a serious breach of the containment structures housing the nuclear fuel cores in at least two reactors at Japan's Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station, as well as potential dangers at several other plants in the region.

Indeed it is also a race to find reliable, real-time public information about the rapidly changing Japan nuclear power emergency, amidst a sea of confusing, conflicting and often limited information emanating from sources across the world. Dealing with the aftermath of the monstrous earthquake and tsunami, as well as the nuclear crisis, has clearly stretched Japanese government and company officials to the breaking point, and their communication has frequently failed to keep up with the story. At the same time, the media covering the Japan's nuclear power situation, on the ground and around the globe, face a challenging array of often-unconfirmed information and speculation.

Of immediate concern is the prospect of a so-called "meltdown" at one or more of the Japanese reactors. But part of the problem in understanding the potential dangers is continued indiscriminate use, by experts and the media, of this inherently frightening term without explanation or perspective. There are varying degrees of melting or meltdown of the nuclear fuel rods in a given reactor; but there are also multiple safety systems, or containment barriers, in a given plant's design that are intended to keep radioactive materials from escaping into the general environment in the event of a partial or complete meltdown of the reactor core. Finally, there are the steps taken by a plant's operators to try to bring the nuclear emergency under control before these containment barriers are breached.

In the Three Mile Island accident, a partial core meltdown occurred in one reactor unit but remained largely within the plant's containment barriers and little radiation was released to the environment. The Chernobyl catastrophe, however, resulted in a massive environmental release of radiation following a core meltdown. An important distinction is that the Chernobyl plant lacked crucial containment structures found at the Three Mile Island and Japanese plants.

Severity scale

According to the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale, which rates the severity of nuclear power plant incidents on a scale from zero to 7, Chernobyl was rated a 7, the highest level of severity and the only such accident. Three Mile Island was ranked a 5, "an accident with wider consequences." Thus far, the Japanese nuclear emergency at Fukushima Daiichi has been rated a 4, an "accident with local consequences," but this is of course a preliminary estimate.

On CNN's Reliable Sources show Sunday, host Howard Kurtz raised questions about the difficult balance between legitimate concern and fear mongering in the around-the-clock coverage of an evolving emergency. Radio host Callie Crossley criticized the repeated media warnings of possible nuclear meltdown: "Nobody told me what it meant....I thought that was extremely irresponsible." Guest Mike Chinoy, a former CNN Asia correspondent, countered that the media "don't have the luxury of putting something together....This is a scary story."

A key challenge is deciding what sources are the most credible in terms of new information about what is actually happening at Japan's nuclear plants and deciphering how serious the situation really is or might become. It almost requires a checklist to follow where the information is coming from; which nuclear plants are in danger; and who is at greatest risk (which will undoubtedly continue to change in hours and days ahead).

-- Some key sources: In Japan, the primary source of information about the damaged nuclear power plants comes from Japanese government officials, with Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano providing regular news briefings; there is also the Japan Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency; and local officials, who provide additional, and sometimes, conflicting information. The main utility company operating the damaged nuclear plants is Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). Some of the most reliable information is coming from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), to which Japanese authorities must report. Reports involving unnamed "officials," which CNN and others used frequently this weekend, should be handled with caution.

--Breaking news from Japan: Other key sources of real-time information include live USTREAM coverage from Japan on NHK WORLD TV, an English language 24-hour international news and information channel; NHK also has breaking news in English; as does Kyodo News agency. There are numerous threads on Twitter, including #fukushima, #nuclear, #earthquake, and #Japan.

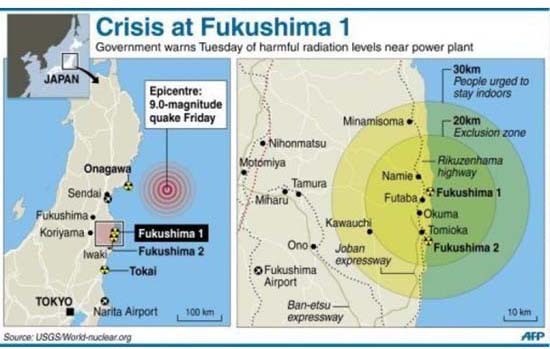

-- The nuclear plants at risk: There are 55 operating nuclear power stations in Japan (see map). Each plant may have multiple reactor units. At this point, the largest concerns involve reactors 1 and 3 at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station (see New York Times graphic). Cooling problems have also been reported at the nearby Fukushima Daini nuclear power station. Preliminary radiation increases were also reported to IAEA from the Onagawa nuclear plant, and news reports have mentioned a fourth possible plant at risk.

-- For a clear backgrounder on how a nuclear power plant works, see the excellent BoingBoing "Nuclear Energy 101" piece by Maggie Koerth-Baker. She said she wrote it in response to a reader who said: "The extent of my knowledge on nuclear power plants is pretty much limited to what I've seen on The Simpsons."

Cristine Russell covered the Three Mile Island accident as a reporter for the Washington Star. She is an award-winning journalist who has written about science, health, and the environment for more than three decades and a Columbia Journalism Review contributing editor on science and the media. This article was published in The Atlantic on 15 March 2011. For all the author's links, go to The Atlantic.