At the beginning of March, Kiribati experienced several king tides in Tarawa. Reporter Ester T. Kabure wrote a story on their impact (Kiribati Independent, 13 March 2015. No. 104). under the heading "Ti bon tuangiia, ma aki kan ongo" (we told them, they didn't bother). Following this article, the editor, Taberannang Korauaba reflects on how government, civil society and the media can work closer together.

ANALYSIS: Few studies have explored the role of the media and communication in Kiribati, apart from what I wrote in 2007 with a dissertation entitled “Problems facing the media in Kiribati: The Way Forward” and later in 2011 with a thesis titled “Media and the Politics of Climate Change in Kiribati: A case study on journalism in a disappearing nation”.

My work is researched-based, others are not as they have only reflected the personal experiences of the authors. I was taken aback by a number of training workshops in Kiribati purported to assist the media and civil societies sharing and exchanging information in the hope of suggesting better and more useful ways to inform the public.

I was taken aback by a number of training workshops in Kiribati purported to assist the media and civil societies sharing and exchanging information in the hope of suggesting better and more useful ways to inform the public.

We expect results and improvements but in Kiribati, the results are nowhere to be seen.

For the context of this commentary, “media” which I am referring to in my article is newspapers and radio.

The state TV was shut down in 2013 due to serious financial problems with no signs that it would be reinstated anytime soon.

How important is the media to the government and policy makers and vice versa, and how critical it is to carefully and thoroughly construct a message for communication to the public has not yet been realised despite common agreements everywhere that the media is important.

Understanding important

However, understanding the public is also important if we want to get them involved.

Sadly on my part as a media and communication researcher for Kiribati, I have not seen any solid evidence to suggest that the main players in the dissemination of information such as government, policy makers and the media have worked together, collaborated or worked in partnership.

The disconnect between these bodies has left the public as the disadvantaged participants in decision making, or as “invisible” citizens.

Participation is central to democracy, and in countries such as Kiribati the role of the media and communication is only explored, or engaged in, when there is a need to do so.

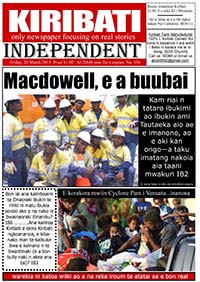

Following last month’s strong king tides and the impacts of Cyclone Pam, many were completely taken by surprise. It was very destructive, and in essence the country was not prepared.

I wrote in my commentary at the Pacific Media Centre website arguing that what happened then shows a big gap between government’s priorities today and the future.

For instance, government’s long term policy does not really relate or connect to the short and medium term problems of the country. High Tides happen several times a year, and people, and more importantly the government should be ready for that.

‘Risk information’

I am aware that communicating “risk information” to the community may not be easy for several reasons which have been confirmed and supported by empirical studies.

People will become sceptical only if we fail to do our homework. In this case, government communicators have not done their homework, and the media have also misunderstood their roles here in the communication of risk.

Exploring these options and alternatives requires expertise, knowledge about media and communication in Kiribati - not in Fiji, not in Samoa or Australia, it should be in Kiribati.

Some will argue with me that there isn’t any media and communication knowledge for Kiribati, we learn and apply theories and debates about the media elsewhere and then apply that to Kiribati.

This is a misconception and it needs to be corrected. Let’s break down Kiribati media, communication and society and see how we can connect the players together so the message they are sending will be received appropriately and action will follow:

1. Kiribati’s population lives in Tarawa and Betio. More than 50,000 people live in these two islands. The people as we all know have their own priorities, so we can’t expect them to sit in front of their radio waiting for warning messages, or to wait for the next papers to publish warnings from the Office of the President.

The radio starts transmission in the morning at 6am and breaks at 9:30am, then it starts a lunch show from 12midday to 1.30pm, and the last show starts at 5pm and ends 9.30pm. Newspapers are printed every Friday. For the people on the outer islands, radio is their only means of getting messages from the capital.

2. We now look at the employees of Radio Kiribati. None of them have journalism or communication qualifications, they have experience, something they learn on the jobs. Internet is not widely used and there have been complaints from the public regarding the slow speed of the internet, and the sale of the public owned Telecom to a private business from outside the country.

Landlines and mobile phones are usually used for business, family and work reasons, they have not been explored as an alternative means to get message across.

3. The Office of the President Press Unit employs qualified people, none of them have tertiary qualifications in media or communications. The MET office and the Climate Change policy team sits under the umbrella of the President’s Office.

While the employees are experts in their own field, they lack solid and theoretical skills in media and communication in their own country. The release of information from these offices require the approval of the Secretary, if the Secretary is on an overseas trip or on leave, the Deputy is in charge, if the Deputy is absent the Officer In Charge will be responsible, if the OIC is out from his office, no one can release that information – so we have an “information shutdown”.

That’s how all the government’s departments have operated since independence. Information is regarded the as the Secretary’s own property, failure to comply with such bureaucratic policy may result in the employees sanctions etc. Many prefer to be an “anonymous source” if they are spoken to by the media.

4. The Kiribati people do not have to share one value, view, belief etc. The people of Kiribati come from different islands, culture and religious beliefs.

For example, those in the South are more strict, their society is based on “individualism”, the central people are more social, and those in the north have a culture of sharing other people’s properties.

Then we have different churches, some are more influential than others, people regard their church as a gift from their ancestors, shifting sides, or converting to another church is seen as a breakaway from family and may result in expulsion of that member from the whole family.

There is an invisible dispute and competition among the churches in Kiribati, a fight and struggle for membership base. Communicating risk to the people who strongly believe more in the Biblical teachings may not be easy.

People in Kiribati, like many elsewhere around the world, resort to the supernatural power of God if they can’t find answers themselves. This is further strengthened by the “we will be alright” attitude.

Other priorities

Bringing together the people to support one message is not going to be an easy endeavour because they are already different, have different hobbies, some are illerate and cannot read the newspapers, some don’t have radio, others prefer to listen to radio news from overseas etc.

So how can we insist on informing the public when inside their heart and minds, they have other priorities? Why should we continue to only use radio and newspapers when we know that they have little impact?

In order to get a message across to the wider community, senders and message constructers must be well informed, must be expert in this area. No wonder why the bureaucracts always complained about “inaction” from the public because they know very little about media, communication and the public?

What strikes me, and which I found to be a distorted argument, is bringing outside experts to train our journalists and communication people.

While they are the experts in their own right, I am not sure how can they apply their knowledge from outside to Kiribati’s circumstances? When people are invited to give presentations or to deliver a training workshop in Kiribati, the very obvious recipe to get the job done, is to flip through the pages of Pacific history book to find a section on Kiribati, undertake last minute quick searches on Google to learn about the islands.

I wonder which article, whose studies, they use to inform their learning? Is it possible to learn about the islands in a few hours or a few days?

What is the people’s attitude to the media and communication in Kiribati, and what is the attitude of the media and communicators to the public and government or vice versa?

I wrote all about these in my dissertation in 2007, and in my thesis in 2011. Yet the trend continues with no signs that the media scene is improving in Kiribati.

For example, the closure of the only television should ring alarm bells that the Kiribati government doesn’t bother about supporting media.

And as for outside media experts, we may be tempted to go deeper and look at the history of the media somewhere else as our example to Kiribati’s case.

I strongly suggest that Kiribati is not looked at as just one package, but to unpack it using the locals’ lens. No wonder we continue to see reports from outsiders that always say Kiribati (but it is pronounced as “Kiribaz”, “Kiribass etc) because the islands are not just strange to them but the dialects and language are also quite tricky.

Self-defeating view

It is not uncommon to hear excuses such as “we told them, they didn’t bother; we announced that on the radio, they didn’t care, we printed our warning in the paper, they didn’t read it.”

In my view, this statement is self-defeating and not just that but it also clearly implies to me that the public are so naïve, didn’t dare to listen at all.

As a media and communications researcher, I would argue that this should give government people and the media the opportunity to review their communications strategies, how can they work together to navigate more alternative communication channels that are appropriate for the public and within the resources of the country.

An updated version of Kiribati Independent editor and publisher and Pacific Media Centre researcher Taberannang Korauaba’s commentary published recently in his newspaper.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND MEDIA ETHICS

Part 1: David Robie and Jan Sinclair

Part 2: Taberannang Korauaba