ANALYSIS: Capacity building is often central to the design of aid programmes and national government policies. However little attention is paid to the obverse, capacity destruction. There is scant recognition in either the international literature on development or in the advice proffered by multilateral and bilateral development agencies that once public institutions are severely damaged through neglect and ideological fixation rebuilding is very difficult, if not impossible. The University of Papua New Guinea, once held up as an example of foresight and future importance but now in a near-terminal condition, provides an opportunity to examine how institutional capacity is wrecked. Consider this a preliminary account which might be informative for UPNG’s future and that of other public institutions. In Part 1 of this account, the promise, as well as inherent weaknesses, of UPNG’s initial establishment are outlined. In Part 2, the deliberate neglect and destructiveness of government policies and international advice are shown.

Part 1: Establishment and post-independence limits - The early years

The University of Papua New Guinea was a well-known late addition to the institutions bequeathed to the soon-to-be independent nation-state. As the UPNG New Guinea Collection’s contribution to the 20th anniversary celebration of the university’s founding notes, the university was the result of a major shift in colonial policy. This policy had previously emphasised the importance of primary and secondary education.

However, with self-government approaching, official opinion increasingly recognised that the change `would not be viable without professionally educated men and women capable of developing and running their own country’. 1 As will be shown later in this account, what was understood in the 1960s was forgotten later when in the 1980s the World Bank ignored intelligent advice and emphasised primary education.

The university was established with the best of intentions by late colonial developers who understood the importance of a national secular university for a secular state. An available large area of vacant land at Waigani, some distance from the port and capital Port Moresby was selected.

If the land, around 1000 acres, was to be the university’s major physical asset, the location at a considerable distance from shops and entertainment, especially at night, would not always prove to be an attraction for the student population housed in dormitory accommodation.

When I asked Dame Rachel Cleland, the wife of the former Administrator, if Sir Donald Cleland and Sir John Gunther, the men who approved the site, would have factored in the then isolation of the campus, her response was to the point.

As two older men, social life appropriate to younger people would not have been considered. In later years, the hothouse atmosphere of campus life which has contributed to many outbreaks of unrest would suggest that the choice of a location was not without negatives.

Nevertheless initially the university seemed to be living up to its principal objective, with important politicians, public servants and commercial figures educated there before and after Independence in 1975. Staffing by expatriates, many of whom had broad international experience, ensured that the student population received what could be termed a liberal education, aware of the most important issues of the day.

Nationalist concerns

This education meant that the university was a focus for the nationalist concerns of both critics and supporters of the late colonial drive for independence. Funding levels increased and the student population expanded after the early modest budgetary support.

When I taught at UPNG between 1983 and 1985, the library had an exemplary collection with a purchasing budget that strained the capacity of librarians to order, catalogue and shelve new books and journals. The current state of the library bears no similarity to that available for students and staff two and a half decades ago.2

While the university’s founders rejected affiliation with any specific Australian university, along the University of London British overseas model, the close early connections with the Australian National University continued after Independence.

That this has been a very mixed blessing will be emphasised below: for now it is sufficient to point out that the closeness between the primarily postgraduate and research ANU, one of the most privileged funded universities in Australia, with the largely undergraduate UPNG has continuing deleterious consequences.

A more serious effect for UPNG’s future came from international university hiring controversies of the 1970s and early 1980s. It is often forgotten that the nationalism of that period affected staff recruitment at universities in the major industrial countries as well as at those being established as centrepieces of newly independent nation-states.

One of the most extreme cases of which I am aware occurred in staff hiring at a Canadian university, where a nine point scale was formulated to determine preferences in recruitment. The most desirable, point one on the first level, was for a Canadian trained at a Canadian university.

The second level of the scale was for anyone but a US citizen, with each of the three points referring to the connection between candidate nationality and training, with the non-Canadian applicant trained at a Canadian university point one and a US university point three.

The third level, also with its three point divisions, had an American trained at a US university as the least desirable candidate, or point 9. As funny as this may now seem, similar if less extreme expressions of radical nationalism occurred at universities in many countries.

At UPNG, the principal effect of this nationalist upsurge was to stress the necessity of appointing citizens as quickly as possible, to indigenise the university, often without much consideration of the skill levels of the appointees.

In case the earlier period is considered an aberration from which lessons have been learned, the current process to recruit a Vice-Chancellor for UPNG suggests that this is not so.

Limited advertising in local papers with the ad written to discourage non-nationals from applying characterises what is now underway to fill the most important position at the university which aspires to be internationally acclaimed.3

The slide begins

During the 1980s, the university began to suffer as the local elite, for whose education the institution had been initially constructed, shifted their focus. With the takeover of formerly foreign-owned plantations and other commercial operations completed, many wealthy Papua New Guineans began to look overseas for further investments. At the same time as maids and house servants were imported, the ruling class’s school age children were sent to educational institutions outside the country.

As nationalism became more important for staff recruitment, the PNG wealthy became less concerned with national allegiances.

This shift coincided with the increasing influence of international ideas which urged reductions in tax and in public expenditure, the effect of which began to bite in the decline of health and education facilities.

The advantages of privatisation as an international drive could be taken up by the elite anywhere. It was a universal policy which encouraged politicians and senior government officials alike to downplay the importance of PNG public hospitals and educational institutions.

That much of the wealth which PNG politicians and commercial figures accrued during this period came from the plundering of state assets simply made it easier to justify sending offspring out of the country to reside in real estate purchased in Sydney, Brisbane and other cities. Being educated at UPNG or in-country at any level became a stigma rather than an accolade in elite circles.

From the late 1980s, the Bougainville crisis and the loss of revenues as well as jobs at the mine accelerated the financial crisis being felt at many public institutions, including UPNG.

With coffee prices at historic lows, the capacities of many rural households to pay fees for education and health were also stretched. At the same time population increases and the extension of aspirations for university education intensified pressures to expand the number of places at UPNG and other public tertiary institutions.

This demand pressure increased as universities, including UPNG became less important for elite education and more significant for training skilled workers and managerial personnel.

Part 2 of this account shows how the destruction of UPNG has continued over the next two decades, to the point where the university would be almost unrecognisable to the founders and the students who attended during the founding years.

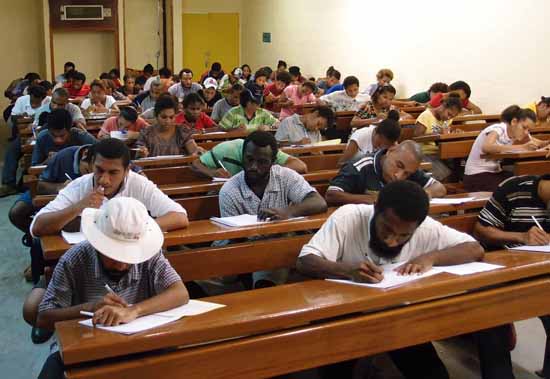

The changes have also meant that hard-working staff and enthusiastic students try to teach and learn in conditions which are unacceptable for any university hoping to produce an internationally recognised quality education for its undergraduates.

Notes:

1. Griffin, Andrew and de Courcy, Catherine (n.d.). The University of Papua New Guinea 1966-1986. Port Moresby: Hebamo Press, p.1.

2. See MacWilliam, Scott (2010). Two Visions and What needs to be done. Pacific Media Centre Online

3. MacWilliam, Scott (2012, June 4). Rebuilding the University of Papua New Guinea. Development Policy.org

© Copyright 2012 Scott MacWilliam