Megan Hutching

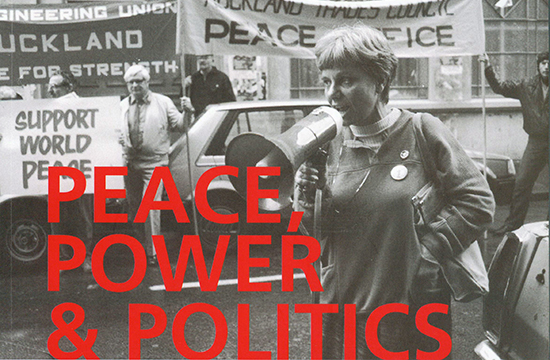

REVIEW: Maire Leadbeater begins her book Peace, Power & Politics by writing that it tells the story of how "ordinary people created a movement that changed New Zealand’s foreign policy and identity as a nation" (p. 9).

The Introduction is useful – it provides the parameters for the book and discusses what "peace" and "peace movement" mean to the author in the context of the campaign.

Leadbeater mentions that there is a strong, but small, pacifist tradition in New Zealand and that there had been vehement opposition among a small proportion of the population to New Zealand’s involvement in the United States war in Vietnam. She rightly reminds us of the effect of the explosion of the two atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 on the thinking of those who opposed war, and how many people who would not necessarily think of themselves as anti-war were appalled by the devastating consequences of these bombs and came to oppose their further development and use.

There had been opposition to visits by United States ships to New Zealand ports in the 1960s – a reflection of opposition to the war in Vietnam perhaps, rather than that some of these ships were nuclear-powered. There was opposition in New Zealand to the testing of atomic bombs in the Pacific by the French in Moruroa and Fangataufa, by the British in Australia, and by the United States in the Marshall Islands, and allied with this, was research work on United States military bases in New Zealand and what they were being used for.

While the book focuses on activities rather than people – which perhaps is a good idea in such a small country with so few degrees of separation – some people are mentioned by name – Owen Wilkes and Nicky Hager’s research roles, George Armstrong’s role in the establishment of the peace squadrons. For me, as a member of a long-established women’s group whose members were (and are) heavily involved in opposing nuclear weapons, it does seem rather a blokey account of activities – there is not much mention of women or women’s groups.

Helen Caldicott's impact

Having said that, Leadbeater does remind us of the impact of Helen Caldicott’s visit to New Zealand in 1983, organised by Kate Dewes (Chapter 8).

There was strong media interest in Caldicott’s visit because of a controversy about the film of one of Caldicott’s lectures, "If You Love the Planet". The United States government had ruled the film "propaganda" and forbidden its showing in the US without permission for the US Justice department. This was obviously censorship and was much criticised around the world.

Caldicott’s lectures were extremely effective. She would tailor her talks to the location and give a graphic account of what would happen if a 20-megaton bomb had exploded in the vicinity. This included such information as "At 32 kilometres [from ground zero] people would be turned into missiles by winds pulling oxygen to fuel fires near the centre of the blast" (p. 84). Her lectures always ended with a call to action, especially to parents because she believed that nuclear disarmament was the "ultimate parenting responsibility" (p. 85).

The effect on the audience was electrifying, particularly on women, and increased the number of women who became involved in the anti-nuclear activities taking place during these years. Leadbeater recalls her own involvement in Women’s International Day of Action for Nuclear Disarmament on 24 May 1983 when 20,000 women marched up Queen Street in Auckland to a rally in Aotea Square (pp. 85-6), and mentions the activities of LIMIT, whose members were particularly good at using street theatre to illustrate their point. It is good to see mention of the Pramazons too, who spread their message via puppet shows and made the connections between colonisation and militarism.

One of the strengths of the book is that it links nuclear-free activism to decolonisation. Chapter 5 covers the Nuclear Free Pacific Conferences held in Suva, Pohnpei (Ponape) and Hawai’i and the establishment of the Pacific Concerns Resource Centre, based in Honolulu, but with centres also in Vanuatu, Belau and Otara, Auckland. Leadbeater is good at using quotes from interviews to illustrate her narrative. Hilda Halkyward-Harawira reflects that the Nuclear Free Pacific Conference held in Hawai’i in 1980 made such an impact on her political beliefs that it:

fuelled me for many years ahead ... As a Maori I understood the grieving of indigenous peoples for the theft of land and the subjugation of culture ... [A]ll the nuclear extractions and testing took place on indigenous lands and the nuclear powers were cold and calculated when they deemed indigenous lands and lives worthless and disposable. For many of the Pacific nations they felt the only way to be safe from the nuclear colonial threat was to be independent from foreign powers who subjected them to this terror. (pp. 61-2)

Chapter 15 deals with the Kanak independence movement in New Caledonia, the massive pressure put on Belau by the United States government after the former adopted a nuclear-free constitution, and the struggle to establish a South Pacific Nuclear-Free Zone. Leadbeater rightly notes that New Zealand governments in the 1980s did little to challenge colonial control in the Pacific.

Focused successful campaign

Peace, Power & Politics is an account of a focused campaign which was ultimately successful. Leadbeater writes that New Zealand politicians ended up reflecting the public’s will on the issue of visits by nuclear-powered and/or armed ships, and opposition to the establishment of nuclear power plants in the country.

The activism to get the nuclear-free legislation is well documented, and the book does tell the story that Leadbeater refers to in her introduction, but it reminds me of Michael King’s one-volume history of New Zealand, which was terrific on what he knew most about, but more of a once over lightly on other things.

In the case of Peace, Power & Politics the narrative is often focused on activities in which Leadbeater took part, but weaker on other aspects of the campaign. An example is the space spent on the Kanak independence struggle in New Caledonia, but little mention of the independence movements in Tahiti Polynesia. Chapters on the anti-frigates campaign and on opposition to the first Gulf War do not deal with how New Zealand became nuclear-free but are rather a reflection of the history of anti-militarism which the book morphs into as it reflects the differing directions in which activism went after the nuclear-free legislation was passed in 1987.

It is a nice-looking book. The pages are laid out well and there is plenty of white space to do the text and the illustrations proud. Leadbeater is to be commended for her careful referencing – especially of the illustrations. She has made good use of private collections of photographs, of cartoons and of posters, and these add a liveliness to the book.

The book also includes a chronology, which is to be commended, and a useful bibliography.

Megan Hutching is a freelance historian and oral historian with a particular interest in women’s peace activism in New Zealand. She is a member of the Aotearoa Section of the Women’s International League for Peace & Freedom. WILPF's conference on militarisation in the Pacific begins at AUT on Friday.

Peace, Power & Politics: How New Zealand became nuclear free

Peace, Power & Politics: How New Zealand became nuclear free

By Maire Leadbeater

Otago University Press, pbk, ISBN 978-1-877578-58-8