Pacific island journalists need to go beyond their traditional “watchdog” role in order to effectively carry out their functions and have a more constructive role in their communities, says a regional author and media educator.

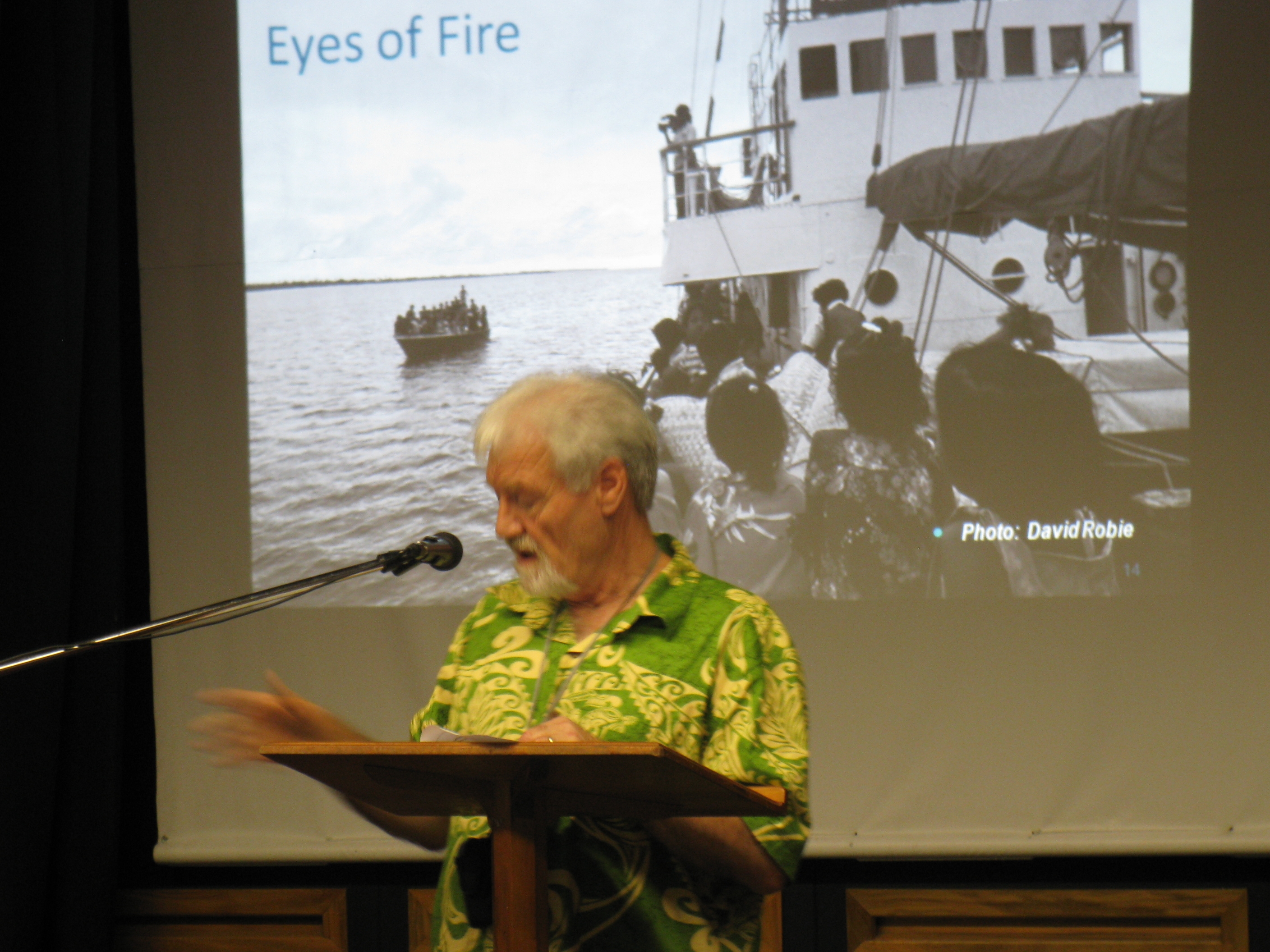

Associate professor in journalism David Robie, director of the Pacific Media Centre, said this at a symposium on the “Role of media and civil society in strengthening democracy and social cohesion'” at the University of the South Pacific in Suva.

Dr Robie said the so-called conventional view of journalism – watchdog on power, bringing facts to light, uncovering abuses – was important but not enough to contribute to a successful democracy.

“Society needs more from the media,” he said, adding that “citizens must also deliberate about policy”.

“In other words, an informed citizen is not necessarily an empowered and active citizen,” said Dr Robie, former coordinator of the journalism programme at USP.

He argued for a stronger contribution to solutions in the Pacific rather than adding to problems.

Dr Robie gave a comprehensive overview of peace journalism in a Pacific context and he cited several advocates of the concept, such as Associate Professor Jake Lynch, director of Sydney University’s Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies and the co-authors of a new benchmark book on the topic, Peace Journalism, War and Conflict Resolution.

Powerful force

In his presentation entitled “Peace-building and development: What role for the Pacific media?”, Dr Robie said the mass media alone was not the “prime instigators of peace or violence” in their communities.

But it was a powerful force in determining how communities identify and deal with disagreements and tension.

Pointing out the scepticism often harboured by journalists about change and reform of their craft, Dr Robie said that regarding peace journalism, subtle shifts in “seeing and thinking” the news rather than radical change was needed.

“Journalists’ objectivity conventions serve to marginalise voices calling for peace, restraint and dialogue,” Dr Robie said.

He added that the media could either strengthen democracy – or undermine it. But in war journalism, the media generally undermined it.

“War journalism can undermine democracy and perpetuate war because it can act as a justification of violence. War journalism concentrates on body bags – not people’s psychology, sociology or culture,” he said.

Peace journalism, on the other hand, instilled greater understanding about the nature of conflict and conflict resolution and clarified types of conflict that led to violence.

'Impartial news'

A common misconception among journalists was that peace journalism aimed to hide or reduce conflict but Dr Robie said the intention was to “seek to present accurate and impartial news”, as it was often through good reporting that conflict was reduced.

“In this definition, good reporting includes information that ‘creates opportunities for society at large to consider and value non-violent responses to conflict”, he said.

Dr Robie said Pacific journalists needed to acquire better “analytical skills” and that the journalism profession should “remain critical of forces that perpetuate media repression”.

He added that peace journalism or conflict-sensitive courses were needed for journalists to provide greater context.

In response to a question from the audience, he said much journalism failed to provide answers to the basic question “why” – why was the conflict happening and what was needed to resolve it.

Dr Robie gave as an example how Chilean authorities had brutally suppressed indigenous Rapa Nui lands rights protesters on Easter Island earlier this month and of 342 stories carried at that time in the international media, very few reports actually explained the background and context.

He praised a report on the Māori Television current affairs programme Native Affairs as being the first in-depth account that provided context.

Media should not blame any ethnicity, but reporting should constantly explain underlying causes of conflict and offer hope for resolution, he said.

An earlier version of Dr Robie’s paper is being published in the latest Journal of Pacific Studies.

Other keynote speakers included publisher and chief executive of Tonga's Taimi Media Network, Kalafi Moala, and senior lecturer in journalism and communications at the University of Queensland Dr Levi Obijiofor.

How 'peace journalism' surfaced in the Pacific

Peace Journalism, War and Conflict Resolution - Richard Keeble, John Tulloch, John and Florian Zollmann, Florian (editors)