The inherent Pacific diversity makes a mockery of the naive mainstream view that there are certain ideal types of “one size fits all” Western models of democracy which non-Western states must fit into, writes Professor Steven Ratuva.

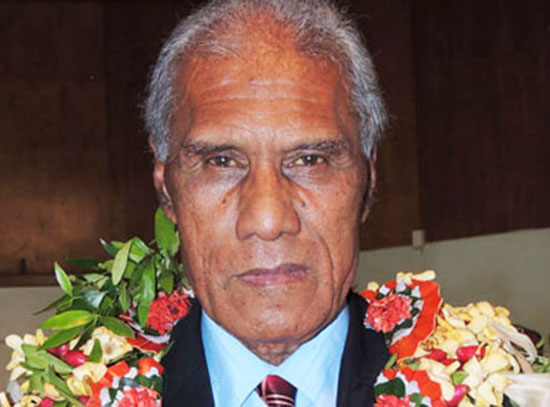

ANALYSIS: As the first elected prime minister of the kingdom of Tonga, ‘Akilisi Pohiva, the long-time Tongan pro-democracy campaign leader, has redefined the meaning and form of Tongan democracy in a significant way.

It is a new phase in the challenging historical evolution of Tongan political rule since 1875 when the kingdom’s constitution was born.

The riots and burning in the capital Nuku’alofa in 2006 brought to the fore the urgency for reform.

The election in Tonga was just one of the few in the Pacific in 2014 (New Caledonia on 11 May, Cook Islands on 9 July, Fiji on 17 September, Solomon Islands on November 19 and Tonga on November 27).

I only had time to observe the Fiji and Tonga elections because of my full international travel and research itinerary.

These Pacific Island countries have remarkably different types of political systems and brands of democracy, shaped by their specific historical, socio-cultural and socio-political realities. This inherent diversity makes a mockery of the naive mainstream view that there are certain ideal types of “one size fits all” Western models of democracy which non-Western states must fit into.

Democracy must not be seen as an end in itself but a process, a continuous and proactive process which should involve adaptation, transformation and consolidation over time.

It’s a political journey with challenges and hopes, anxieties and optimisms.

For Tonga, Pohiva’s election is part of that journey, it is not the end of the journey but the beginning of a new one.

Electing the prime minister

The long awaited election of the prime minister on December 29 involved a long and onerous process which took about a month since the November 27 general election. Unlike other parliamentary democracies where the prime minister assumes office immediately after the election following necessary protocol, the Tongan Constitution is more relaxed on this issue and provides for a “caretaker government” in the interim. Clause 51 states:

“Following a general election…Ministers shall be and remain as caretaker Ministers until their appointments are revoked or continued on the recommendation of the newly appointed Prime Minister.

“…and during such period caretaker Ministers shall not incur any unusual or unnecessary expenditure without the written approval of the caretaker Minister for Finance.”

Within 7 days of the declaration of results, the king has the constitutional duty to appoint an interim speaker who will then call for nominations for the position of prime minister 10 days after the return of the writ of elections and the nominations are to be received 14 days after the return of the writ of elections.

The interim speaker will then convene a meeting of elected members within 3 days of receipt of nominations to elect the prime minister. This constitutionally prescribed process tends to be time consuming and slows down the formation of the new government.

This is more so given the absence of formal political parties and constitutional provision for the majority party to form a government immediately after the election. Even then, the distribution of seats between the three major political groupings in parliament (nobles, independents and pro-democracy) did not provide for a clear majority in 2010 and 2014.

Of the 26 members of Parliament, 9 are reserved for nobles who elect themselves and 17 are by the people. The people’s representatives are divided between the members of the Democratic Party of the Friendly Islands (DPFI), Pohiva’s pro-democracy group and those referred to as “independents” who, because of lack of any coherent political grouping, are able to shift their political allegiance as the circumstances demand.

Turned their backs

After the 2010 election, the first under the amended 2010 Constitution, the 5 elected independents aligned themselves with the 9 nobles and managed to form a government. They were of course rewarded with cabinet posts. This time around 6 of them turned their backs on the nobles in a dramatic U-turn and realigned themselves with the 9 pro-democracy parliamentarians.

This won Pohiva 15 votes as opposed to 11 votes for Samiu Vaipulu which consisted of votes by 9 nobles and the 2 remaining independents. The post-election horse trading among the elected politicians in Tonga is a political art in its own right.

Because no one commanded the absolute majority of 14 seats to form a government in the 26 member parliament, at least two of the three groups were needed to form an alliance of sorts. Intensive negotiations took place between the independents, who saw themselves as holding the balance of power, independently with both the nobles and pro-democracy group.

The negotiations were on the basis of “win-win” pragmatism rather than on ideological convergence. A direct coalition between the nobles and the pro-democracy camp would not have been possible because they were natural ideological enemies.

An attempt to incorporate Pohiva into the noble-led government as Minister of Health in 2010 did not work out because of irreconcilable differences. Buoyed by their electoral success in 8 constituencies (an increase of 3 seats from the last election), the independents had hoped to form the government either with the nobles or with the pro-democracy group which lost 3 seats from the 12 they won in 2010.

Their proposed prime minister was Samiu Vaipulu, the then Tongan deputy prime minister, who was also endorsed by the nobles, who hoped to come back to power, even by compromising on the prime minister position held by Lord Tuivakano, a noble representative.

Plan rejected by nobles

However, attempts by some independents to endorse Siaosi Sovaleni, a very popular Tongatapu (Constituency 3) representative, to become deputy prime minister was rejected by the nobles who felt that having a commoner prime minister and commoner deputy prime minister would further erode their power and dominance in government.

This led to a classic political maneuver which saw Sovaleni and five others from the noble-independent alliance shifting support for Pohiva’s pro-democracy group. They were dully rewarded with four ministerial portfolios.

This left the 9 nobles isolated and for the first time in Tongan history, were deprived of formal political power through the parliamentary process.

The only consolation was Lord Ma’afu’s appointment as Minister for Land, a position which is normally reserved for nobles primarily because most land in Tonga is owned by either nobles, monarch or government and commoners are allocated plots by the landed classes through lease or other forms of feudal-type traditional arrangements.

With a comfortable majority on his side and with a new ministerial line-up consisting of some young and well qualified technocrats whom Pohiva will reply on to drive the ailing economy forward, the challenge is to redefine and reform Tonga’s development strategies amidst the burden of heavy debt (45 percent of GDP), poor growth (less than 1 percent) and more transparency in governance.

Pohiva’s recent statement that “Tonga needs a Bainimarama” to drive the reform forward may ruffle feathers among the privileged, landed gentry and conservative classes who may attempt to create barriers to undermine Pohiva’s reforms to maintain their privileges and interests.

Tonga’s electoral system

Like many other Pacific island countries such as Cook Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, Tonga uses the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system where the winner is declared after a candidate collects more votes than the others.

For the popularly elected seats, there are 17 single member constituencies where boundaries are drawn on the basis of both geographic convenience and demographic distribution.

One of the criticisms of the FPTP electoral system by experts is that the winners are often declared with less than 50 percent of the votes and this is often considered unrepresentative.

This is the reason why many countries have opted for other electoral systems such as the Proportional Representation (PR) where seats are allocated on the basis of proportionality to the votes or Alternative Vote (AV), where votes are traded between candidates and winners get more than 50 percent (plus one) of the votes.

In Tonga, the only 2 winners who actually polled more than 50 percent were ‘Akilisi Pohiva with 53.5 percent in the Tongatapu 1 constituency (a decrease of 10 percent of the votes from 62.5 percent in 2010) and Sosefo Vakata who polled 54.6 percent (the highest in the country) in the Ongo Niua 17 constituency (the smallest constituency).

The winner with the lowest percentage was Penisimani Fifita with 25.3 percent for the Tongatapu 9 constituency.

The low percentages were to be expected given the relatively large number of candidates and small number of voters. The largest constituency was Tongatapu 10 with 3035 votes cast and the smallest was Ongo Niua 17 with 949.

Democracy in action

Reforming the electoral system to make it more representative is something which may need consideration for the future as Tonga’s democracy evolves further. Nevertheless, the great thing about the FPTP system is that it is very easy to administer unlike the PR and AV systems which can be complex and at times confusing.

It should be noted that there were actually 3 elections before a prime minister was finally chosen. The first was the popular vote for the 17 seats and the second was the election by the hereditary nobles.

The nobles had their own kinship-based alliances which they used to mobilise support.

Rather than ticking the names of nominated candidates, the nobles simply wrote down the names of their preferred candidates on a blank ballot paper. In case of a tie, methods such as flipping of a coin or drawing match sticks (as was the case in 2010) could be used.

The third election was the parliamentary vote by elected representatives to choose the prime minister. There is a growing opinion among the pro-democracy supporters that nobles have to subject themselves to popular vote like everyone else.

Others have suggested a separate upper house for nobles similar to the British House of Lords. The strong connection between culture and politics in Tonga as in other Pacific Island countries like Fiji and Samoa is increasingly being subjected to critical scrutiny, especially the way in which cultural status and privileges are used to sustain and justify political power and wealth in the modern and changing society.

Should the natural phenomenon of birth be used to determine one’s success in life or should there be a level playing field for everyone to ensure that success is based on personal capability?

These are some of the questions which underpin the Tongan reform agenda and indeed Pohiva’s thinking as Tonga progresses through another phase of its democratisation.

Election as cultural festival

Apart from its serious implications, perhaps one of the highlights of the Tongan election for me was the carnival-like atmosphere before and after the polls when processions consisting of dozens of decorated cars thronged the narrow streets of Nuku’alofa, the Tongan capital.

It was a political Heilala Festival of sorts where festive euphoria reigned, a contrasting situation from the normally sober and tense mood one sees in other elections around the Pacific.

The pre-election processions were by supporters of the different candidates who crossed paths and waved to each other humorously as they passed each other.

But the post-election victory celebration procession in Nuku’alofa was dominated by Sovaleni’s supporters in more than 30 decorated cars playing loud music and dancing joyously to a mixture of English, Tongan and Fijian tunes.

The processions may appear confusing to outsiders who are used to thinking about elections as tense and potentially violent affairs as we have seen in other parts of the world and in the Pacific where post-election public celebration is kept to a minimum to avoid violent clashes among political opponents.

In Fiji, while there was a public thanksgiving church service by the supporters of the victorious FijiFirst, there was no Tonga-type festive euphoria because of fear of invoking tension.

The sociological symbolism of the Tongan public procession was more than what first impression suggested. It was an opportunity for the people to connect and mobilise their sense of community and express their feelings of Tonganess in a culturally symbolic way.

For a moment, political contestation was temporarily subsumed by collective expression of communal cohesion in the common belief that everyone was working towards a common end-democracy. Whoever won hardly mattered because they were all united by the fact that all the candidates, whether independent or pro-democracy were collectively people’s representatives.

It had the latent effect of reducing tension by transforming political anxiety into festive psychology. It was a great lesson in conflict resolution for the rest of the Pacific and the world for that matter to learn from.

Pohiva and the future of Tonga

Beyond the euphoria of the festivity are the stark realities of economic stagnation, indebtedness and governance challenges which need fixing.

Many years ago, over a glass of beer, I told Pohiva, a long-time friend, that he would one day become prime minister of Tonga.

His ambition and resolve to transform Tonga has not withered a bit despite several hiccups, progressing age and unsuccessful attempt to lead the government in 2010.

Some of his supporters began to lose hope because the reform under the 2010 constitutional amendment did not achieve much by way of leadership change and he even lost 10 percent of his support base.

Pohiva’s election as PM will no doubt ignite a new flame of enthusiasm, hope and support as one could observe in the Tongan online discussion forums. To many Tongans, Pohiva has become a living political martyr who was expelled by the government from his teaching job, imprisoned, suspended from Parliament, faced countless court cases, demonised as trouble maker and psychologically brutalised by a powerful ruling class bent on exorcising Tonga of Pohiva-type political heresy.

But now the same ruling class will have to live and work with its nemesis, the man who tried to curtail their excessive power, the man they tried to destroy but failed, the man who through democracy has risen to become Tonga’s second most powerful man.

Second only to His Majesty.