No matter which region of the Earth we look at, we see the same 60–80 percent of all disasters as being climate disasters. This means that governments, national disaster-management agencies and local communities can all think about what types of disasters they are most likely going to face. They need to plan and allocate resources for these, writes Dale Dominey-Howes.

ANALYSIS: While the impacts and effects of Tropical Cyclone Pam on Vanuatu are still being revealed, important lessons are beginning to emerge in relation to disasters in the Pacific region.

At least 24 people have died in the Vanuatu capital Port Vila, but there are no casualty figures from outside the city yet.

At Category 5, Cyclone Pam was a very severe tropical cyclone with reported wind speeds of up to 300 kilometres an hour. However, it is not unique in that this region of the central South Pacific has experienced similar severe tropical cyclones in the past.

That said, given greatly increased development and infrastructure in low-lying Pacific islands, the effects of cyclones like Pam are much larger than they have been in the past.

Basically, we now have more people, infrastructure and assets “exposed” on the ground in places where tropical cyclones make landfall.

From a disaster risk-management perspective Cyclone Pam is not at all unusual. It is exactly the sort of disaster we can expect to impact a region like Vanuatu and the South Pacific.

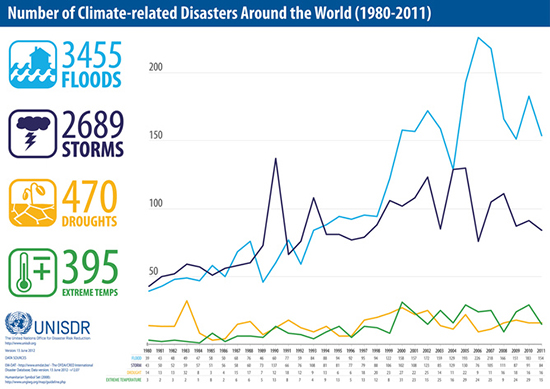

Statistics from the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) show that globally something like 60–80 percent of all disasters (the exact numbers and percentages are actually not easy to assess) are what we call “hydro-meteorological” – that is related to extreme weather and climate events, as you can see in the figure below.

No matter which region of the Earth we look at, we see the same 60–80 percent of all disasters as being climate disasters. This means that governments, national disaster-management agencies and local communities can all think about what types of disasters they are most likely going to face. They need to plan and allocate resources for these.

Anthropogenic climate change is expected to change the frequency and intensity of weather and climate-related extreme events, so future weather and climate-related disasters will also change – likely increasing, although trends are different for different hazard types.

Was Vanuatu well prepared?

Conflicting reports are swirling about the media concerning whether Vanuatu’s government and its communities were well prepared or not.

This is especially significant given Vanuatu President Baldwin Lonsdale is currently in Japan attending the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction. The answer depends on who you are and your perspective.

A very emotional President Baldwin, speaking at a press conference on the morning of March 16 in Japan, stated clearly that “not many lives have been lost and that this is a credit to pre-planning and early warning”.

This may or may not be true. Only post-disaster surveys and assessments in the coming days and weeks will determine if this is the case.

However, despite downplaying potential loss of human life, Baldwin repeated over and over that extensive devastation to homes, infrastructure, built assets, farm and agricultural resources and products had occurred, significantly impacting on recent development gains achieved by Vanuatu.

Looking at early television images coming from Vanuatu, it is clear that extensive damage has occurred. From the perspective of residents and business operators, Cyclone Pam has been a complete disaster, destroying homes and businesses.

The effects will be prolonged given the importance of the tourism economy in Vanuatu. Loss of destination infrastructure has ripple effects through the economy that can and will last months to years, affecting the GDP of the country.

In work funded by AusAID, our team has shown that the negative perceptions for tourists that can result when disasters strike otherwise tropical island paradises are extremely problematic for countries like Vanuatu. We’ve also done work on Pacific nations such as Vanuatu and Samoa, all of which need to adapt their tourism industries to climate change and disaster risk.

For NGOs it is a mixed bag. Pre-planning means many NGOs had already distributed their post-disaster response materials (food, water, blankets, shelter materials etc) at strategic points throughout the Vanuatu islands before Cyclone Pam arrived.

This potentially makes emergency response distribution easier and faster – an excellent planning initiative. Only the next few tens of hours will determine how effective this strategy has been.

Sharing the responsibility

Vanuatu and Cyclone Pam is an example of what I call the “tyranny of scale” in relation to disaster risk management.

Vanuatu, like most Pacific Island nation states, is a so-called “small island developing state” with widely spread, low-lying islands, a small population, limited growth and asset commodities.

This means scale acts against these governments and communities, stretching resource allocation and complicating post-disaster response activities.

In some ways, there are lessons for a continent country like Australia. We have a reverse scale issue – a massive continent, with remote and widely spread small communities across vast areas. How do governments get response assets to remote communities that might be cut off and isolated for days or longer? And who is responsible?

These are legitimate questions. In past decades it tended to be the case that governments and their emergency management agencies served the community and were perceived to be there to help when things went wrong and disasters struck.

In reality, as the world becomes a more developed and complicated place, the take-home message is that we need a shared responsibility for disaster planning, response and recovery – a responsibility shared between individuals and their families, communities and our governments and emergency services.

With limited emergency resources available to governments and their agencies, increasingly it is unreasonable to expect our governments to be completely there for us. This is the case with the survivors of Cyclone Pam now as they begin to put their lives and communities back together while waiting for government and the international community to do their part.

Dr Dale Dominey-Howes is associate professor in Natural Disaster Geography at the University of Sydney. Republished from The Conversation with a CC licence.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand Licence.