The really important question is how we respond to terrorism. The humanity demonstrated by those who held vigils on the streets of many capitals around the world after the Paris killings was deeply touching and symbolically very important. But it is just the start, writes Simon Reich.

ANALYSIS: I grew up in London during the IRA bombing campaign of the 1970s. I lived in Pittsburgh during the 9/11 attacks when United Flight 93 was forced down not far from the city. I’m currently in Paris where I live part of the year.

Each of these cities is filled with decent, thoughtful, moderate people: people who care about their families, their communities and their country.

They may argue vehemently about politics, religion and sport. But what binds them, overwhelmingly, is their commitment to a modern set of values, liberal-democratic values that its proponents collectively define as “modernity and progress”.

These values are not unique to what their adversaries call “the West”. These values were just as evident among those Arabs and Muslims who protested in the squares of Cairo and Tunis. Those who began the war against Assad in Syria. Those who demanded greater rights in the streets of Hong Kong. Those who clamor for recognition on the streets of Moscow.

Unfortunately, in these cases, the protesters were outnumbered and crushed by adversaries who control the military and the police. They were defeated by politicians who can whip up a frenzy among people who fear the future rather than embrace it.

Always threats

In each generation, we collectively face a threat from people who value control and conformity rather than freedom of expression. The source and form of these threats take many forms and those that carry them out vary in their goals.

The Cold War sought to impose a statist political system. Jihadists want to impose a medieval one masquerading as a religious one. But they share common features. They seek to divide and conquer, to rule and impose their values. They seek to quell freedom of thought and action.

Sometimes the threat is widespread and realistic. Soviet missiles really did pose an existential threat. Sometimes it is more symbolic.

The Paris shooting, like the IRA in London and 9/11 fits in the latter category. The target was well-defined, and carried out barbarically and with efficiency. It was the quintessence of terrorism.

Sadly, we will always face such threats. And they will always hit soft targets.

The really important question is how we respond. The humanity demonstrated by those who held vigils on the streets of many capitals around the world after the Paris killings was deeply touching and symbolically very important. But it is just the start.

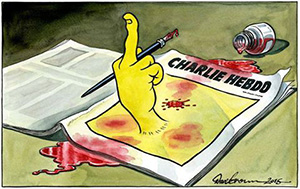

What to do? Shock and sadness will inevitably give way to indignation, anger and a desire for revenge. The scale of the attack on Charlie Hebdo was much smaller than 9/11. But it would be foolish to underestimate the effect of these killings on the French national psyche, a country that was spared the post 9/11 bombings in London and Madrid.

Shock and sadness will inevitably give way to indignation, anger and a desire for revenge. The scale of the attack on Charlie Hebdo was much smaller than 9/11. But it would be foolish to underestimate the effect of these killings on the French national psyche, a country that was spared the post 9/11 bombings in London and Madrid.

So how will we respond to each other when the shock has subsided? Today, as I write this story, France is preparing for a moment of silence and the streets of Paris are eerily silent. But will France be able to distinguish the real enemy from those we think look like the enemy in the months ahead?

After 9/11, Muslims and people who looked like Muslims (which included Sikhs in turbans to the more ignorant) suffered discrimination at the hands of unscrupulous politicians and violence at the hands of thugs looking for someone to blame. Many Europeans, living in the throes of mass unemployment, are prone to the same temptation – to blame someone, anyone, for their individual and collective woes.

As I sat on the train last night after the attack, there were two women sitting near me. One was an older woman who wore a traditional head-dress. She looked down, unwilling to even acknowledge a man sitting opposite her.

The other was a young woman with make-up, painted nails, a short skirt and high-heeled boots. They were obviously both Muslims. These were clearly nobodies’ enemy. Neither is my sister-in-law’s partner, a Jew whose family is from North Africa – and who can be mistaken for an Arab Muslim.

France’s National Front party, led by Marine Le Pen, has already embarked on a cynical course, denouncing Islam as the enemy. The FN is not alone. Michel Houellebecq, one of France’s most renowned authors, coincidentally published a novel yesterday entitled Submission (in English). Its central plot is that France has become an Islamic state in which civil society capitulates to Sharia law.

Prior to the attack, it was the talk of France.

Humanitarian values

It is tempting to buy into this narrative, one of a clash of civilisations. Europeans from Greece to the UK are ready to do so. But we shouldn’t. Our common cause is with those who embrace common humanitarian values, even though we disagree about so much.

Our enemies are those who reject these values. Both our allies and adversaries come in every color and proclaim every religion. It is time to get tough with those who oppose our common values. We’ve been too willing to let others divide us on the basis of colour, wealth, religion or politics.

Getting tough doesn’t have to entail fighting more wars, mass imprisonment or the use of torture. The Spanish didn’t discriminate against a whole minority group when it fought ETA – and ultimately ETA faded away.

Real toughness means demonstrating the resolve showed by the English when they faced the IRA bombing campaign in the 1970s and 1980s. It entails the kind of dignity showed by those who held vigil in Paris’ Place de la Republique the night of the attack.

It entails showing fortitude by sticking firmly with the values that have served us all well over the course of the last several centuries.

Otherwise, whether we defeat the Jihadists or not, they will have won.

Dr Simon Reich is professor in the Division of Global Affairs and The Department of Political Science at Rutgers University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence.