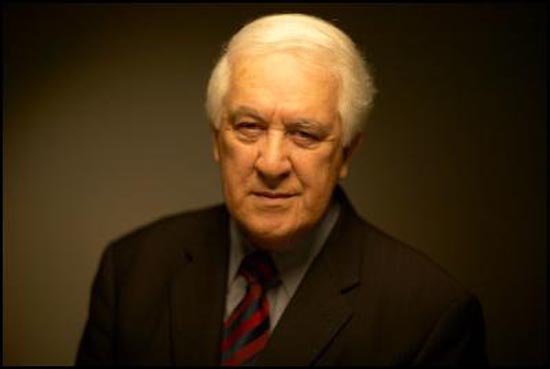

TRIBUTE: Sir Paul Reeves (RIP) contributed enormously not just to his Māori community, but also to the wider Pakeha community in New Zealand. That remarkable ability to transcend the ethnic barriers within New Zealand also saw the international diplomatic community calling on him to help in resolving ethnically divided and strife-torn communities in South Africa, Guyana and Fiji.

I write briefly on his service to Fiji, although more will be written by others who have a more intimate knowledge.

To understand the difficult political challenges which Sir Paul faced and overcame, one needs to understand the debilitating century-old ethnic politics in Fiji, which eventually also undermined the work that Sir Paul Reeves did.

With indigenous Fijian-led parties dominating government since independence in 1970, the first Indo-Fijian one (led by Jai Ram Reddy, Timoci Bavadra and Mahendra Chaudhry) was, within one month, deposed by the 1987 Rabuka coup.

The racially biased 1990 Constitution, ensuring perpetual indigenous Fijian control of Parliament, was established with the full support of all the indigenous Fijian institutions, including the Great Council of Chiefs and the Methodist Church.

In the mid-nineties, Sir Paul Reeves was made Chairman of the Commission of Inquiry into a new constitution for Fiji, to supersede the 1990 Constitution. The “Reeves Commission” also had one Fijian representative (Tom Vakatora) chosen by the Rabuka government, and one Indo-Fijian representative (Dr Brij Lal, from the Australian National University), chosen by Jai Ram Reddy.

Tom Vakatora was an experienced civil servant and later minister in various governments, as well as a Speaker of the House of Representatives in Parliament. Dr Brij Lal was a historian prolifically documenting the history of Indo-Fijians since their arrival as indentured laborers in Fiji in 1879.

Balancing views

Sir Paul therefore had the unenviable task of balancing what appeared then to be irreconcilable points of view. Outsiders who had observed very strong Māori expressions of support for the Rabuka government may have even thought that Sir Paul Reeves, a Māori, might sway towards the indigenous Fijian points of view. But what Sir Paul and his colleagues achieved was astonishing, in bringing together sharply opposing views into a consensus report that was generally accepted and used as a basis for the 1997 Constitution, passed by both Houses in Parliament.

But what Sir Paul and his colleagues achieved was astonishing, in bringing together sharply opposing views into a consensus report that was generally accepted and used as a basis for the 1997 Constitution, passed by both Houses in Parliament.

While there were some important modifications by the 1998 Parliament (of which I was then a member) they in no way altered the real substance of the Reeves Report contributions to the 1997 Constitution:

That a consensus report was written at all, was a credit to Sir Paul and the mutual rapport he had with Tom Vakatora and Brij Lal, enabling all three commissioners to come to a middle ground acceptable to the Fijian and Indo-Fijian parties, following widespread consultation with ordinary Fiji citizens through the length and breadth of Fiji.

That the report was accepted in the House of Representatives was due to the enormous work done in building a historical partnership between Jai Ram Reddy (who took along the National Federation Party with him, despite the misgivings of many of his colleagues) and Sitiveni Rabuka (who took along the SVT likewise). This partnership gave hope to Sir Paul Reeves about the future of Fiji and the Reeves Report built on it.

That the 1997 Constitution was passed by the Upper House was due to the leadership of Rabuka who overcame much opposition from the provinces, which doubted the value of any power-sharing with Indo-Fijian leaders but developed respect for Jai Ram Reddy who was the first Indo-Fijian leader to address the Great Council of Chiefs.

The only criticism I had of the Reeves Report (voiced in The Fiji Times of 1 and 2 November 1996, “The Reeves Report: sound principles but weak advice on the electoral system”) was that the Alternative Vote system, for all its benefits, was not suitable for Fiji. I thought (in addition to other criticisms) that it would marginalise small parties, while strengthening the large extremist parties. Sadly, these fears were all realised in the elections in 1999, 2001 and 2006.

Some quibbled about the lack of “one man one vote” but the Reeves Commission recommended an adequate blend of “Open” seats which were effectively “one man one vote” constituencies) and “Communal” seats (to reassure the major ethnic groups). The Fiji Parliament in the end decided on more Communal Seats but still left 25 Open seats (out of 71). (The behavior of voters in these Open seats was no different from their behavior in the communal seats.)

It was quite spurious of the claim by 2006 coup supporters (such as the Fiji Labour Party in 2007), that the 1997 Constitution was racist because all the seats were not “one man one vote” (the same allegation continues to be made by Bainimarama today).

Power-sharing element

Even the Alternative Vote system was not a drawback to sound parliamentary governance, as the 1998 Parliament had approved a power-sharing element which was not in the Reeves Report – a multiparty provision which ensured that all parties with at least 10 percent of the seats, must be invited to join cabinet.

It was a tragedy (and probably a historical turning point for Fiji) that the Fiji Labour Party, having won the majority of seats in the 1999 elections, chose to exclude the Fijian SVT from cabinet.

That decision undid all the good work that had been done by Sir Paul Reeves and his commission, and all the generous compromises that Rabuka and the Fijian politicians had made in accepting the 1997 Constitution, which ironically lost them control of Parliament.

It was not surprising that most Fijian politicians felt a sense of betrayal over the 1997 Constitution. The 2000 coup took place, with an inhuman prolonged hostage crisis suffered by Chaudhry and his colleagues.

Bainimarama ended the hostage crisis, but rather than reinstalling Chaudhry’s government, he appointed an interim Laisenia Qarase Regime. The 2001 elections took place and were won by Qarase’s newly formed SDL Party.

The 1999 decision by the Fiji Labour Party to exclude the major Fijian party (SVT) was then reciprocated in a “tit-for-tat” measure by Qarase and SDL which offered FLP minor ministerial positions, understandably rejected by the FLP.

However, after the 2006 elections, Qarase and SDL offered good ministerial positions to the Fiji Labour Party which accepted them, but with their Leader (Chaudhry) choosing strangely to not just remain out of Cabinet, but also trying to become Leader of the Opposition.

Bainimarama coup

It was this 9-month-old multiparty SDL/FLP government, that was beginning to work reasonably well, which was deposed by the Bainimarama coup of December 2006 – not, as claimed simplistically by coup supporters, a “Qarase government”.

Soon after the 2006 Bainimarama coup, to the shock of international observers, Chaudhry and his Fiji Labour Party joined Bainimarama’s military regime, and thereby also obtained widespread support from the Indo-Fijian community and religious organisations. But Chaudhry was sacked by Bainimarama after a year in unknown circumstances.

The other military regime ministers and important post holders have been drawn from a Fijian party (National Alliance Party of Fiji) which won not a single seat in the 2006 elections (but which included former military commanders) and very strangely, some leading supporters of both the 1987 and 2000 coups. (The story of who exactly from the army were involved in the 2000 coup, is only now slowly unravelling).

After the 2006 coup, Sir Paul Reeves was called upon, as a Special Representative of the Commonwealth Secretary-General, to try to convince Bainimarama to return Fiji to democratic rule, even after the April 2009 abrogation of the Constitution.

He failed, but not for want of trying, several times.

Sir Paul Reeves’ apparent failure in Fiji will not in any way reflect badly on his efforts. Any current failure is more a sad reflection on the poor calibre of some politicians who have sacrificed the public good for personal interests at critical times in Fiji’s history.

Test of time

That may also be said of the current set of military ministers who turned down the very moderate proposals by Sir Paul Reeves in 2009, in order to continue to rule Fiji by military decrees, a Public Emergency Decree renewed monthly (when there is not a hint of public emergency) and draconian media censorship.

It will be an interesting test of time, to see whether the alleged abrogation of the 1997 Constitution by an army with the authority of guns, will last when the voters of Fiji eventually have the freedom to elect their own Parliament and decide which constitution they want, using the authority of their votes.

I suspect that the 1997 Constitution, which embodies the work of Sir Paul Reeves and his Constitution Commission colleagues, will one day rise like a Phoenix from the ashes, to vindicate the moderating work of a decent man, who has always seen beyond ethnic differences, to the common humanity of all.