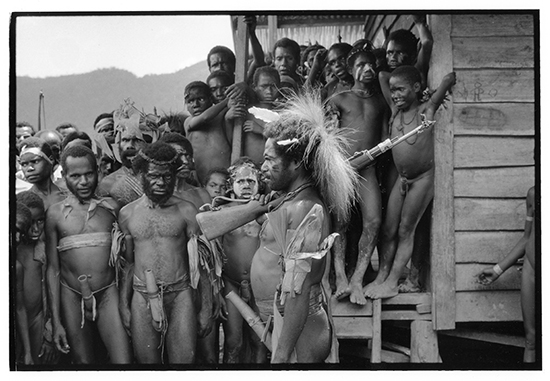

Australian photographer/writer Ben Bohane’s new monograph Black Islands: Spirit and War in Melanesia is the manifestation of his vision to document the culture, wars and islands beyond the borders of Australia. The book is the culmination of Bohane’s dedication to photograph under-reported Pacific issues and history. By Tamara Voninski of IPA.

PROFILE: From your perspective as an Australian photographer and writer based in Vanuatu, is Australia a continent island or part of the Pacific Islands? Why?

I have always been slightly troubled by this notion that Australia is a continent, as if we are removed from our immediate geography. The reality is, if we choose to see it the way earlier generations of Australians did – that Australia is just a big Pacific island, forever connected by the blood and song lines of our indigenous people and our long relationship with our immediate Melanesian neighbours. Modern multicultural Australia has forgotten the importance of the Pacific islands and our shared identity and destiny with it. Just look at the map. Australians have become so globalised that they have forgotten their own backyard, yet for a photojournalist like myself, there are incredible stories here that need to be told to Australians, instead of our news constantly dominated by the wars of the Middle East and the “boom” of Asia.

The introduction to Black Islands: Spirit and War in Melanesia, states ‘the Pacific as a whole represents 30 percent of the world’s geography, yet remains the most under-reported region on earth’. What led you to move to the region and report the events and daily life in Melanesia?

From 1989-94 I covered conflict in Asia and southeast Asia, in places in Burma, Cambodia and Afghanistan. From 1994 onwards I moved into the Pacific because I could see that no-one was really covering it. I first started by covering Australia’s proxy war in Bougainville and got first pictures of rebel leader Francis Ona, which I did as an exclusive for TIME. That trip opened me up to all sorts of other, unreported conflicts going on in Melanesia, from West Papua and East Timor to the Solomons and New Caledonia. Things have quietened down in recent years (apart from the ongoing tragedy of West Papua), but from 1994 to about 2004 there was a solid decade of serious conflict in the region which kept me pretty busy. I have stayed covering this region because I love this part of the world and have based myself in Vanuatu for the past 11 years, it’s my sanctuary and a good listening post for the region.

What are some of the extreme challenges you have faced photographing in a region that many see as picture postcard paradise on Earth?

There have been lots of challenges in covering this region, from having to do serious trekking in jungles and mountains, often trying to avoid patrolling armies. There have been dodgy boat trips, hot landings on occupied beaches, and a few near-misses. This is an expensive and logistically difficult part of the world. But on another level, the big challenge is always winning local people’s trust so that I can do the job that needs doing. You can still find the picture postcard beauty of this region, but beneath the surface there are often tribal and land disputes and periodic conflict.

What led to your dedication of your life’s work covering hidden wars and spirit worlds in the Pacific? Can you explain the connection between resistance movements and kastom as a thread throughout your work?

Alot of my friends and colleagues have felt the need to be where the “big stories” are; in places like Iraq, Afghanistan, former Yugoslavia etc. But I always figured that these conflicts where already well-covered, if anything they are a media circus and this is what I’ve spent my life avoiding. Instead I have always focused on doing my reportage in the more forgotten places and wars, places like West Papua which are hugely important to Australia but get very little coverage. Part of the reason I have focused on this region is because I have a particular interest in theology and comparative religion.

Whereever I go, I photograph through the prism of spirituality – theirs and mine – to get a deeper sense of the culture. For instance when I spent many years covering the war in Burma, I spent alot of time with a rebel Buddhist organisation and trying to understand the people by immersing myself in its dominant belief system. Likewise in the Pacific, my focus has been to explore the relationship between kastom (custom) to have a better understanding of the roots of conflict in this region. It has been said that “Melanesia boasts more than a quarter of the world’s distinct religions and presents the most complex religious panorama on earth”. I have been fascinated by its range of kastom, cult and cargo cult movements, as well as watching the rise of Islam and Christian syncretism and it is this spiritual landscape that I wanted to document beyond the wars.

Is the use of sorcery relevant to inhabitants of Melanesia in contemporary society? What role does the diverse range of religion play in the lives of Melanesians?

Melanesia is a 24/7 spirit world. When you come into this region it helps to take off your secular goggles and realise how kastom and ancestral spirits still play a large role in daily life. Sorcery is still a potent force, as we see in the terrible witch burnings of PNG and on-going sorcery-related killings that happen in all countries in this region. Not all sorcery is bad, of course, there is magic to grow your gardens, love magic and healing, but it is usually the sorcery killings which grab headlines. There remains a persistent belief in this region that no death is ever natural – there is always some malignant spirit or sorcerer responsible. Melanesians are themselves always interested in religious ideas and like to experiment, that’s why they were quick to embrace Christianity before and now we see Islam, Bahai and other faiths taking hold, as well as the revival of their own kastom religions.

Your writing and photography utilizes the research methodology called participant action research (PAR). Can you explain what this means and how it differs from typical photojournalism on assignment or documentary photography in the field?

Participatory Action Research is just one of those fancy academic terms which you have to slot into your MA thesis to explain a certain methodology. Basically it just means that wherever I go I have consulted the locals and operate with their consent. My assignments would not have been possible without taking a grassroots approach, a compassionate approach and earning their long term trust. I have built long term relationships in this region and been accepted everywhere I go. Speaking the language (Tok Pisin and Bislama) helps a great deal.

In the forward to Black Islands: Spirit and War in Melanesia you wrote, “thanks to all the black fella communities who took me in and shared their stories and spirits and kept the bullets away.” How did you stay safe when things turned violent? Did you have many close calls with danger?

In a lot of these conflict situations my safety is basically in their hands. You have to be able to trust the people who are guiding and looking after you and pretty much every time they have. In places like Bougainville or West Papua where I was trekking with the OPM guerrillas and moving through their villages, they know that it is in their interests to protect you so you can get the story out, especially when there are so few media who come and hear their side of the story. Sometimes in the highlands of PNG or the urban areas, things can get volatile and unpredictable, so you always have to have your wits about you, and to be with people you can trust to get you through. I’ve had my share of close-calls, getting shot at in Bougainville, deported from Indonesia, and afraid of being taken hostage in Maluku and Guadalcanal by a warlord there. But I always remind myself that whatever I go through is chickenshit compared to what alot of ordinary people have to go through every day when their country is at war. You have to keep things in perspective.

Why did you crowdfund the book Black Islands: Spirit and War in Melanesia on Emhasis.is? Was the experience worthwhile and positive?

I did the crowd funding thing because it was a way of forcing me to set deadlines and rally support so I could publish my book that I was sitting on and wondering how I was going to get published. It worked out for me because it gave me a platform and a 2 month deadline to raise the necessary funds, which tends to concentrate the mind and wallet. I got there in the end and was pleased with Emphas.is although sadly it sounds like they have folded recently.

Did you study religion or theology? What does the spirituality of the Pacific mean to you personally?

I could say that I have been a “student” of philosophy and religion all my life. It is an interest that goes beyond photography but has certainly influenced my subject matter and the way I frame things. I find that by immersing myself into whatever the local belief system is gives you a deeper understanding and empathy for the people you are with and the politics and conflict around you. The life of a photojournalist means you spend alot of time travelling and waiting, waiting, waiting. Having the time to read so many great books in these situations has been one of the joys of life. The life of a photojournalist also exposes you to so many different beliefs and viewpoints – why wouldn’t you become more and more curious and sensitive to the amazing diversity of the world? The Pacific is so rich in this way, inherently spiritual, the connection between people and their land and sea. Alot of modern religion has removed us from nature and our ancestors, but not in this part of the world.

BEN BOHANE is an Australian photojournalist and author who has covered Asia and the Pacific islands for more than 20 years. Much of that time has been spent documenting religion and conflict. He has the largest individual photo archive of the South Pacific in the world. His photographs are collected by the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum and the Australian War Memorial, as well as in private collections. His profile in Pacific Journalism Review is here.

WAKAPHOTOS: wakaphotos.com | degreesouth.com | The book: www.wakaphotos.com/black-island-book/