For three years before the 2013 election in Australia, the Opposition coalition conducted a merciless campaign on two themes. “Stop the Boats” and “Ditch the Carbon Tax” became an incessant chant, with little else on offer. Nauru and Papua New Guinea featured in this “Pacific Solution”, writes Scott MacWilliam.

ANALYSIS: When relations between economically and politically dominant and subordinate countries are described, metaphors are often employed. Australia has been described as a client state of the United States, filling the security role of deputy sheriff in this region for the world’s most powerful nation.

One of the difficulties with such metaphors is that they tend to suggest a static, permanent condition. When relations change, so too must the metaphor.

Such is the case now, when Australian foreign policy has become captive to the domestic and international policy positions adopted by countries which previously appeared subordinate to the South Pacific’s major power.

Such is the case now, when Australian foreign policy has become captive to the domestic and international policy positions adopted by countries which previously appeared subordinate to the South Pacific’s major power.

Australia may be able to convince the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank not to provide loans to the military government holding power in Fiji.

However, the region’s largest country is now in thrall to the governments of Papua New Guinea and Nauru. An important question for the future is which relatively small South Pacific country’s government will next be able to determine how it is treated by Australian governments.

For three years before the 2013 election in Australia, the Opposition coalition conducted a merciless campaign on two themes: “Stop the Boats” and “Ditch the Carbon Tax” became an incessant chant, with little else on offer.

Nauru featured continuously as central to the Opposition’s “Pacific Solution” for the so-called “flood” of asylum seekers or illegal migrants. Papua New Guinea and Manus Island became the second leg of the policy to ensure people who tried to come by boat, usually from Indonesia, were not given residency rights in Australia.

Policy with gusto

While the development of a detention centre at Manus was initially devised under the previous Labor-Greens-Independents coalition government, the current conservative coalition has seized upon the same policy with gusto.

Recognising PNG’s importance to the Australian government which has pinned its electoral future on “stopping the boats”, the government led by Prime Minister Peter O’Neill has played the trump card for all it is worth.

Not only have money flows for the construction and operation of the detention centre and ancillary activities increased, funds continue to be diverted from an already reduced aid budget for the central elements of “Operation Sovereign Borders”.

Under this campaign, led by a senior army officer, the navy is reduced to the role of towing asylum seeker boats back to Indonesian waters or placing refugees in inflatable boats which are then deposited on less populated locations in the archipelago. Navy officers and other ranks were forced to suffer in silence the humiliation of an army officer explaining that all the sophisticated radar and other equipment could not prevent naval ships “inadvertently” sailing into Indonesian waters.

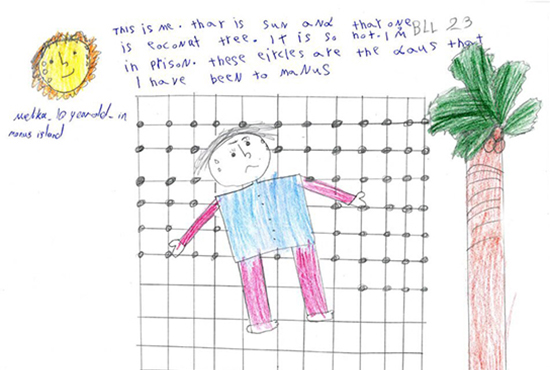

When boats avoid or escape the net and refugees manage to land on Christmas Island or a part of the Australian coast, they are immediately transported to Manus or Nauru for “processing”. Refugee claims, security and health requirements can take years to assess, with detention in both places of an indeterminate length.

Detention camps in both PNG and Nauru are overflowing with refugees who are likely to remain there for years. Riots, escapes and self-harm are common occurrences.

The conversion of aid into border security is made even easier by the hostile takeover of AusAID by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The former agency has effectively disappeared, with many senior AusAID officials gone and the remainder working under the unsympathetic authority of DFAT managers.

Further twist

Even this change in administrative arrangements has a further twist which affects the balance of power between the Australian, PNG and Nauru governments.

Unlike AusAID, for whom such matters as corruption, governance, accountability and transparency were central policy goals, DFAT is more concerned with international relations that advance Australian security and commercial interests in the region.

These interests, as well as PNG’s support for the asylum seeker policy ensure that the relevant minister Julie Bishop visits PNG regularly and is invariably pictured with Prime Minister Peter O’Neill. Not a word is said publicly by either Bishop or her department’s officials about the increasing grand corruption that has become the signature behaviour of the PNG government and administration.

As a Southern Highlands, Hela, Enga and Simbu bloc seeks to displace the previously ascendant indigenous commercial interests the top ranks of the public service and government agencies are now filled by officials from these provinces.

Manus is too important for the minister and government to object to the accumulation practices which Australian foreign policy tolerates and sustains.

What next? While other smaller South Pacific countries are on the Australian radar for the location of detention centres, the next larger country after PNG should not be discounted. Bishop has already flagged a changed policy toward the Bainimarama government in Fiji, even if the details of the shift remain to be fleshed out.

Despite all their previous rhetoric about the need for Fiji to return to democracy, would Australia (and New Zealand) accept an electoral victory by their erstwhile enemy, no matter how this is achieved?

Rigged election

The ties between Australian parties and their Fiji counterparts might ensure that a rigged election would receive some criticism. Nevertheless “Stopping the Boats” and keeping asylum seekers who travel on them out of Australia is of such importance that a conservative Coalition government would easily ride out objections from within the Liberal Party.

In the event of Commodore Bainimarama making a successful transition to elected prime minister, could he make a trip to Australia, and be photographed alongside Prime Minister

Tony Abbott, Bishop and Immigration Minister Scott Morrison? Would the picture be attached to an account of how Fiji has now agreed to establish a detention centre, paid for by Australia with employment for surplus to requirements Fiji military personnel?

And what metaphor would be employed for this change? Tail wagging the dog, perhaps.

A Serco guard's illustrated impressions of life inside an Australian detention centre

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand Licence.