ANALYSIS: In Part 1 of this account, some strengths as well as limits to the University of Papua New Guinea in its early late colonial and post-Independence years were outlined. Part 2 details how the potential has been largely destroyed in consistent attacks on the university’s funding as well as the importance of its place in building and educating Papua New Guineans.

Part 2: Going back to the future: Enter the `knowledge bank’

By the early 1990s, at the same time as more and more households were unable to balance domestic budgets, successive PNG governments were urged to cut expenditure to meet declining revenues. Unsurprisingly petty corruption flourished to follow the large scale corruption of the political and commercial elite.

Also unsurprisingly it was not long until international advice constructed for countries in Africa and elsewhere was urged upon PNG. According to the recommendations, corruption was best addressed through good governance measures, managing the nation’s affairs to bring development as an early description summarised the idea.

Who exactly would localise and implement this international advice, in a context where accumulation as well as daily survival were predicated on corruption, was hardly considered.

The importance of tertiary educated indigenes of the intermediate strata, the so-called middle class who might oppose corruption, demand better service provision and be active in national and local representative institutions was downplayed in two further aspects of the international advice being given to PNG governments.

The first appeared to be a repeat of 1950s colonial policy, though in a completely transformed context, and dominated thinking at the head office of the World Bank in Washington.

This advice urged a renewed focus on primary education.1 Scarce resources should not be wasted on tertiary education since Papua New Guineans could be more effectively educated at this level overseas. While the economic wisdom of such destructive advice was attacked in a scholarly series of papers, and at a conference in Washington by World Bank consultant Tim Curtin, this criticism had little effect.2

Where ignorance is bliss, it is indeed folly to be wise!

Although Curtin’s scholarship and penetrating analysis did not alter the internationally received wisdom, subsequently an equally important consequence of the drive to attack tertiary education has become apparent.

Just as the idea of governance was expanded to include accountability, transparency and openness, with elections being elevated in importance, PNG had a reduced capacity to educate its young people at all levels in what might broadly be regarded as civic virtues.

That there might be an intimate relationship between all levels of education, primary, secondary and tertiary for the inculcation of these values seems to have escaped the sophisticated economists at the "knowledge bank".

In order to further denude the capacity of public tertiary institutions, the World Bank, supported by AusAID, worked to extend the fantasy of privatisation to tertiary education in PNG.

Ignoring the parlous condition of the most important secular public universities in a country where there is no dominant religion and much less religiosity than in other South Pacific countries, the newly established Catholic Divine Word University at Madang became the template for PNG’s future.

That Madang is not the nation’s capital, nor a major commercial centre, that DWU was not the first choice of the country’s brightest secondary school leavers, and that it has never shown any capacity to make the transition from the founding, highly centralised "one man band" administration have all been unimportant for the main development aid ideologues.

The attractiveness of DWU was further enhanced for international advisers and academics looking for an ideal conference venue by Madang’s sea-side location. That it was regarded as relatively safe from attacks by criminals also helped, although this feature has paled after a savage attack against four young Australians engaged in an AusAID volunteer scheme.

Unfortunately for those enamoured with privatisation, what the focus on DWU allowed was a further reduction in government attention to the importance of state expenditure for all public and state subsidised private universities. Tertiary education’s importance continued to be downplayed. Educational standards at all PNG universities continue to slip further below international standards.

To teach or not to teach: that is the question

What the international advice, which suggested that Papua New Guineans could obtain their tertiary education overseas, in part missed is the important distinction between undergraduate and graduate education. The use of international advisers to recommend on future directions for PNG tertiary education with little or no experience of the former and of the important differences between them has reinforced what was lacking in the other advice.3

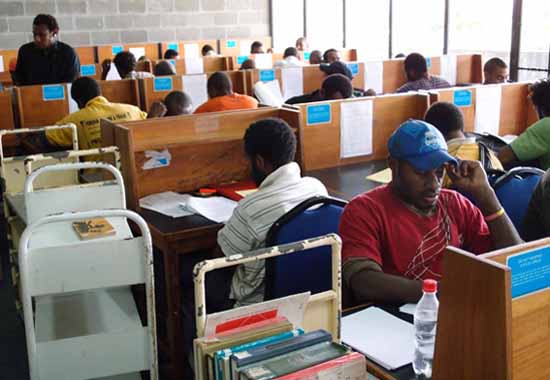

As noted above, since the mid-1980s at least UPNG has become less and less a preparatory institution for the country’s elite and more a sub-standard training facility for skilled workers and managerial personnel.

With this change, it might have been expected that UPNG’s international alliances with similar universities would be strengthened.

Yet, as tertiary education in many countries has developed more distinct divisions between the well-funded graduate and research cum-government advisory universities and the mass teaching institutions,

UPNG’s major associations are with the former rather than the latter. The ANU connection, encouraged by past associations as well as AusAID practices, remains especially prominent. This attachment continues to be strongest with those parts of the Australian university which have few if any undergraduate students and so are least similar to UPNG.

As UPNG’s total income per student continued to be reduced to a small fraction of the allocation from the national budget that had been granted at Independence, its main academic contacts are with institutions and staff least able to or even interested in providing advice on how to teach well under these conditions.

To urge that UPNG seek to emulate a well-resourced graduate and research university, either in whole or part, is irresponsible as well as damaging for the morale of staff at the former.4

Conclusion

It is ironic as well as tragic that at the same time tertiary education, and especially UPNG, has sunk to an impoverished condition, the University of the South Pacific has not been dragged down to such an extent. Australia, New Zealand and Japan have continued to support USP even as some member countries of the South Pacific have made reduced contributions.

Recently the Asian Development Bank and USP have concluded a major loan agreement to improve facilities at several campuses. With this support, USP also retains a programme of external advisors who assist in monitoring courses and degrees.

The funds and personnel provided to a university which draws upon much smaller populations than live in PNG suggest the first lesson from the severely reduced capacity of UPNG and other tertiary institutions in the country. The condition of universities which train people to standards required by current global employment conditions is a continuing international responsibility.

Secondly, there are public institutions which every liberal capitalist state needs to maintain, even expand in downturns as well as upturns in its economy. Knowledge and skills, as well as civic virtues that are nurtured at universities must be reproduced constantly and consistently over generations.

As a wide range of countries practised during the last three or so decades, when economic conditions are least favourable and unemployment rises is precisely the time to expand educational facilities. Not only are young people in educational facilities less likely to engage in criminal activities, they are also more likely to be acquiring skills needed in an economic upturn and for the rest of their lives as active, participant citizens.

Thirdly, public institutions cannot be turned on and off like a tap. Private firms come and go, but strong, effective schools, universities, hospitals and the like have capacities that are not easily or quickly reproduced. As civil wars and more substantial military conflicts invariable show very starkly, capacities destroyed across a generation take many years to rebuild. Far better that instead of acting upon deeply ideological short-term recommendations, such as are still provided by academics and others who attack tertiary education, policy-makers should emphasise the importance of institutional maintenance and expansion.

Finally, in a modern economy it can never be a matter of "bringing the state back in" but that the state has a constant and indispensable presence in the development of labour power. In some countries and to some extent, most notably in Australia, the increased and extensive support for private schools has made it possible to greatly expand their number and enrolments.

Private universities are often also all too ready to seek government attention while benefiting as in PNG from government neglect of public institutions. In a country like PNG with a still exceedingly small middle class there cannot be a substantial private university reliant on fee income that can take the place of UPNG and all the country’s other public tertiary institutions.

When the latter are allowed to suffer death from the ongoing continuous cuts to their annual budgets since 1992, the country is left without any internationally recognisable universities, public or private.

Whether there will be rapid as well as substantial assistance to rebuild UPNG lies in the future. While the lessons from the past may provide valuable guidance for this specific task, of equal importance should be the recognition that public policies may destroy capacity as well as increase it.

Acceptance of the potential destructiveness of state policies does not need to lead to the application of the conservative "do no harm" doctrine. Instead the building, maintenance and expansion of public institutions should always be driven by the opposite objective, do as much good as possible.

Back to Part 1

Notes

1. World Bank (1987). Costs and Financing of Education in Papua New Guinea Washington: IBRD; World Bank (1988). Papua New Guinea: Policies and Prospects for Sustained and Broad-Based Growth, Washington: IBRD.

2. Curtin is a long-time campaigner against the assault mounted since the 1980s on tertiary education. He has systematically documented in publication after publication, dealing with PNG, Australia, South Africa and Britain that tertiary educated people more than pay for the costs of their qualifications in taxes paid. See for example, PNG The Economics of Public Investment in Education in Papua New Guinea. Occasional Paper No.1, Faculty of Education, The University of Papua New Guinea 1991, and more generally Curtin (1996). Project Appraisal and Human Capital Theory, Project Appraisal, June 1996; (1999). Economic and health efficiency of education funding policy (with E.A.S. Nelson). Social Science and Medicine, 48.

3. See for one recent instance PNG Universities Review 2010, the popularly dubbed Garnaut-Namaliu Report. Sir Rabbie Namaliu taught briefly at UPNG in its halcyon days, Ross Garnaut has had no involvement with undergraduate education and is an ANU economist with some graduate supervision experience. For criticism of aspects of the misplaced recommendations of this Report, see MacWilliam University of Papua New Guinea - What Needs to be Done on Pacific Scoop.

4. This unwise direction is advocated in the recent Garnaut-Namaliu Report.

© Copyright 2012 Scott MacWilliam