Why is Robert Fisk so hacked off with the way much of the Western media portrays the Middle East conflicts? Katie Llanos-Small interviews an author who has reported three decades of horror and injustice to find some answers.

“If you're going to go to war, at least go to war led by someone who knows what war is like. I’m not sure McCain does, actually.”

The Independent’s celebrated Middle East correspondent Robert Fisk is discussing his idea that if people saw the true horror of war as he saw it, they would never again support one.

Asked whether this theory might make Republican candidate John McCain – a Vietnam veteran - a better choice as president than Democrat candidate Barack Obama, who has no first-hand experience of war, he is unconvinced.

“I don’t think that that’s necessarily the case,” says Fisk. He describes Ariel Sharon as “ruthless” in spite of his war experience and Winston Churchill as “careful”, perhaps as a result of his.

“[McCain] knows what it's like to be in prison. He didn't fight. He didn't see people blown to pieces… But nonetheless, he was in the war, he suffered, and that has to be acknowledged. It doesn't mean he's going to be a better guy. But it means at least he'll have people who do not see the world through Hollywood.”

The reality of the Middle East compared to the way it is presented to Western audiences is a theme of Fisk’s, common in his talks and his work.

Glossy coverage

He is outraged by Western media’s glossy coverage of Iraq, especially in the lead-up to the 2003 invasion. And few media organisations are safe from his wrath – not even the BBC.

“The BBC was not showing pictures of the worst casualties in Iraq.

“If an Iraqi was obliging enough to die romantically beside the road and [a photo] could be taken at sunset with a romantic glow over it…” he says, his voice bristling with sarcasm.

“The daily grind of horror was missing.

“The BBC says, ‘oh, we're better than Fox’, but if you're still not going to show the reality of war, it doesn't make any difference.”

This correspondent, with more than 30 years experience in the Middle East, takes bad reporting very personally.

Mostly, it’s bad reporting about the Middle East that he gets worked up about. But it seems bad reporting about himself is behind his distaste for the internet.

“My problem is that to me, it’s become a system of hate,” he says.

“John Malkovich says at the Cambridge Union he wants to shoot Robert Fisk. Within hours, blog-o-pops pop up on the internet with pictures of me covered in blood, saying John Malkovich is jumping the queue.

“I go to America and give lectures to thousands of people. I have no security, nothing. It just takes one guy more insane than John Malkovich and I’ve got problems.”

He has been misquoted over and again on the internet, he says.

“You can’t hold the internet responsible… There’s no way you can correct it. You try correcting something on Wikipedia. It’s impossible.”

The power of words

Fisk has lived in Beirut and worked in the region for three decades. Armed with a vast knowledge of area’s history, he fights for justice in his Independent columns, championing the oppressed above anything else.

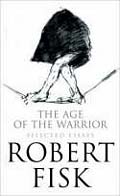

He has a greater awareness of the power of a single word than most other journalists. At a talk organised by AUT’s Pacific Media Centre, Fisk reads an extract from The Age of the Warrior – the book he is in New Zealand to promote.

At a talk organised by AUT’s Pacific Media Centre, Fisk reads an extract from The Age of the Warrior – the book he is in New Zealand to promote.

The article, “Hack blasts local rags”, has the lunchtime audience laughing out loud at the clichéd language of the small town newspaper where Fisk started his journalism career: police “narrowed their search”, Tory candidates “lashed out”, protesters “took to the streets”.

While he was surprised the newspaper had barely changed its writing style in the 40 years since he was on the staff, Fisk lamented that many of his colleagues carried the cliché habit with them.

“One of the things you can do when you switch words around, is ameliorate the truth, and you can also change the nature of the tragedy.”

Many newspapers have come to call Palestinian territories occupied by Israel as “disputed territories”, rather than “occupied territories”; the Israeli-built wall is taller and longer than the Berlin Wall, yet it is called a “fence” or “security barrier”.

“If a Palestinian child chucks a stone, and you know his land is occupied, his father’s land has been taken away for a ‘neighbourhood’, or a colony or a settlement, that there’s a bloody great wall running through his property, you might understand why he throws the stone.

“But if he’s chucking a stone because of a ‘dispute’, over a fence, a garden fence, something you could solve in a law court or over a cup of tea, then obviously that Palestinian is generically violent.

“As we ‘de-semanticise’ the conflict… we make the conflict more lethal, because we make the Palestinians a people without reason.”

‘US officials said …’

Journalists are too often guilty of focusing too heavily on official versions of events, he complains, pulling out a clipping from the Los Angeles Times.

“It's written from Washington; it's about Baghdad,” he says as he launches into the article. He skips between paragraphs, reading aloud underlined phrases: “US officials said”, “US officials said”, “US officials said”...

“There's your problem. You're not going to find out about the Middle East from that, are you?” he huffs.

He doesn’t talk to Western officials, and he rarely deals with those in the Middle East either, he says. Voicing his disagreement with “50/50” reporting – the idea that each article must be balanced between comment from each side – at the PMC lecture, the audience hums in acknowledgement.

Voicing his disagreement with “50/50” reporting – the idea that each article must be balanced between comment from each side – at the PMC lecture, the audience hums in acknowledgement.

“The Middle East is not a football match. It’s a massive, human, bloody tragedy.

“Yes, I think we should be objective and unbiased – on the side of those who suffer.”

Would a journalist give equal time to a Nazi SS spokesman or a slave boat captain, over a holocaust survivor or a slave, he asks.

A journalism student is the first in the overflowing lecture theatre to ask a question: what can journalists do to avoid the pitfalls of the profession that he criticises so greatly?

He stresses they should work for newspapers which will not alter their work before publication, and don’t fall into blogging because it doesn’t have the same integrity as in print.

“Don’t refer to the mainstream press as the mainstream press, and don’t waste your time on the alternative press, because it’s only read by believers.”

Pictures: (from top): Robert Fisk ... exposing Middle East realities, and the crowd at the Robert Fisk talk. Photos: Alan Koon