Sylvia Frain profiles the achievements and challenges of four days at the second Pacific Ocean Climate Change Conference,

Cyclone Gita interrupted the timely and relevant second Pacific Ocean Climate Change Conference held at Te Papa Tongarewa museum in Wellington last week.

I was fortunate to arrive on the last flight before Wellington Airport closed on Tuesday afternoon in anticipation for Gita’s arrival. Many presenters and participants had their flights delayed or cancelled, which solidified the urgency and importance of the conference.

Many presenters and participants had their flights delayed or cancelled, which solidified the urgency and importance of the conference.

As independent researcher and keynote speaker Aroha Te Pareake Mead pointed out, Air New Zealand acknowledges the disruptions and increased storm activities and is currently working on developing digital solutions and asks its customers for patience and flexibility.

While the Pacific Media Centre featured several pieces highlighting speakers at the conference, the pre-conference workshops and public lecture set the tone for the next few days.

The gathering provided a platform for researchers and scientists, practitioners and state representatives to collaborate, share knowledge and plan for the future.

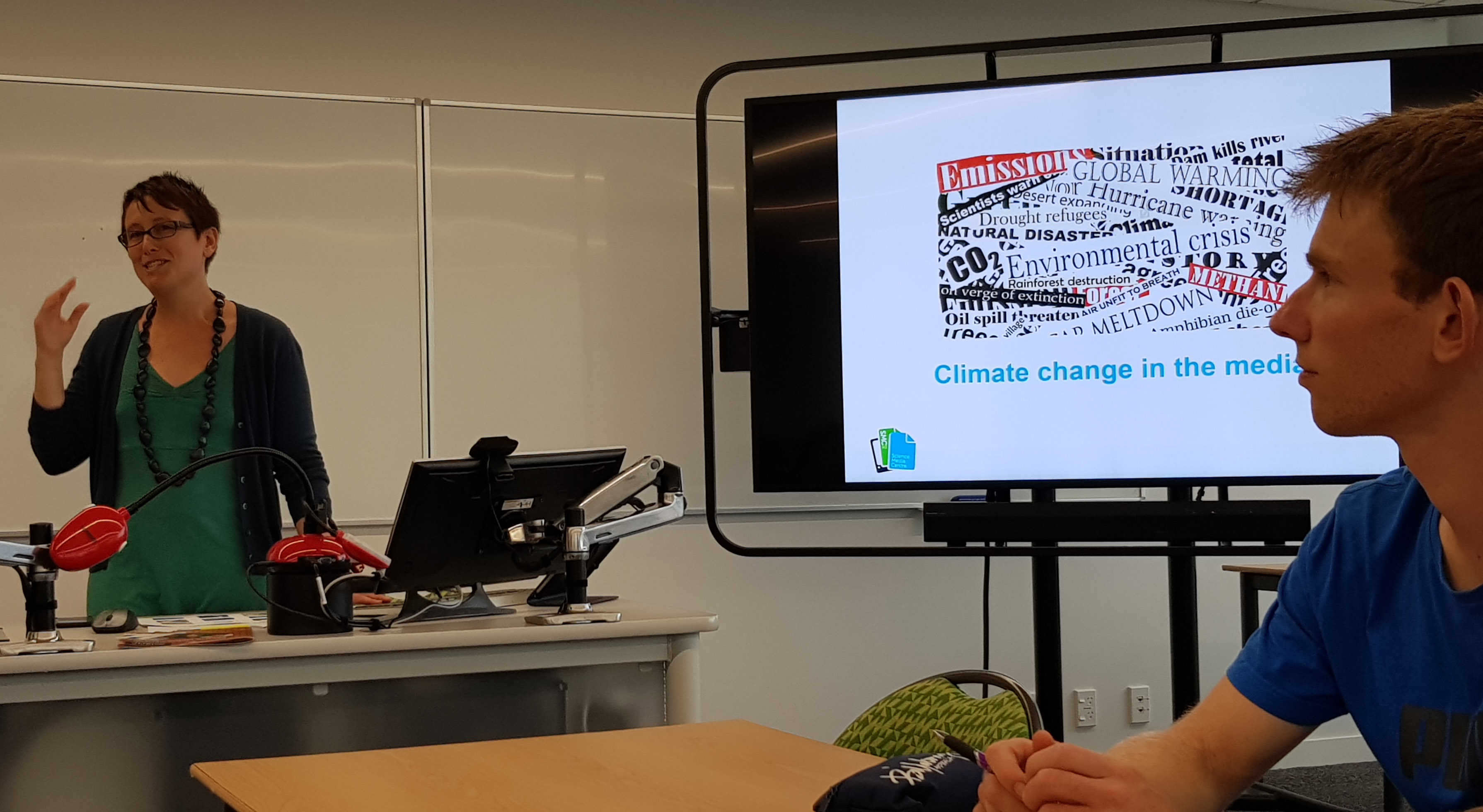

The Climate Change Media and Communication pre-conference workshop, facilitated by Dacia Herbulock, senior media advisor at the Science Media Centre, included media professionals, freelancers, and those using visual and written communications to convey the depth and urgency of climate change.

Visual stereotypes

The visual stereotypes and the challenges of long-term reporting in a fast-paced media environment dominated the discussion of how to best, and most appropriately, make a relatively “abstract” issue seem “real”.

Participants provided practical solutions, including creative strategies and diverse delivery mechanisms for academic researchers to produce text, audio, video, and used new media platforms to reach a wider audience.

Two examples are the interactive piece by Charlie Mitchell, “The Angry Sea Will Kill Us All: Our Disappearing Neighbours” on Stuff, organised in a new multimedia format.

The second online outlet is The Conversation, (the academic and journalism collaboration currently in Australia, and soon to be launched in New Zealand) which provides researchers and academics editorial support and the ability to track and evaluate the online publication’s reach and audience.

While these platforms are improving climate change reporting capabilities, there remains an urgent need to ensure that Pacific and indigenous perspectives are at the forefront directing climate change resiliency and adaption policies.

This is a reminder that current climate change is a contemporary manifestation of colonialism and the continued exploitation of stolen land and resources.

While Pacific and indigenous populations are not the leading contributors to emissions, they are on the frontlines experiencing the impacts disproportionally.

‘Discoveries’ already known

Catherine Murupaenga-Ikenn highlighted how “a significant proportion of [scientific] ‘discoveries’” are not discoveries at all, but that “indigenous peoples already knew about many of these ‘scientific’ ideas”.

She called upon the Western scientific community to follow the example of the World Council of Churches, who in 2012 denounced the Doctrine of Discovery, and “denounce the ‘Doctrine of Scientific Discovery’ as it relates to indigenous knowledge”.

She also invited scientists, journalists, and policymakers “to build good faith collaborative partnerships with indigenous peoples so we can together explore ‘consciousness’ with a view to identifying ‘technologies’ that would help mitigate and adapt to climate crisis”.

She reminded the audience that Albert Einstein said, “No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.”

While the law and legal frameworks can be a tool to encourage states to make commitments to lower emissions and create national standards, there are limitations to enforcement and accountability.

During the pre-conference public lecture, Law as an Activism Strategy, Julian Aguon of Blue Ocean Law, spoke of how he “practices law for change” and “uses international human rights law for self-determination” for Guam.

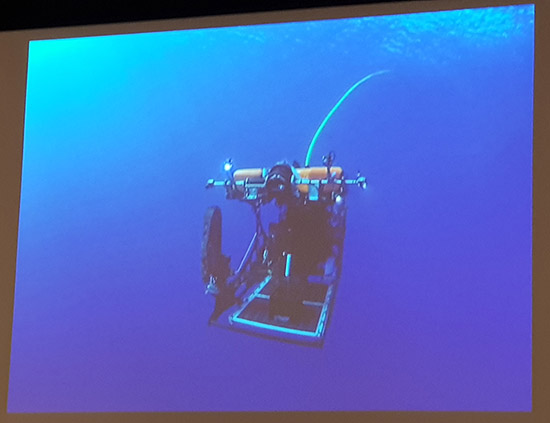

His work is currently focused on deep sea mining, (DSM), an experimental and newly emerging form of mineral extraction.

The Pacific Region is seen as the “latest frontier” which is more politically stable with less potential for conflict than other mineral-rich regions of the globe.

However, the minerals are hundreds of kilometres under the sea - a region that is relatively unknown.

Aguon discussed how scientists know more about the moon’s surface than about deep sea ecologies, hydrothermal vents, and tectonic environments.

Asia Pacific Report coverage of the conference

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3